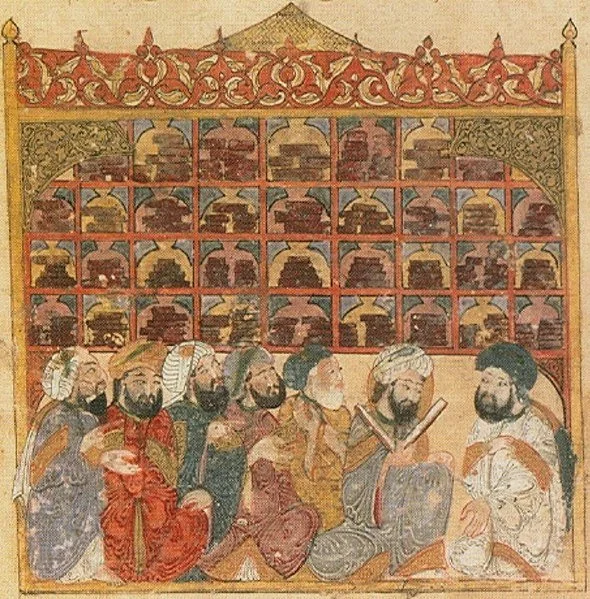

13th-century depiction of scholars in the library. (Wikimedia)

YOU CAN LISTEN TO THIS EPISODE HERE OR ON YOUR USUAL PODCAST APP.

Quote:

“Keep this in mind: knowledge leaves a trail, a trace of scent that leads to its possessor; it sheds a brightness, too, a brilliance that both illuminates and reveals its bearer … as when someone walks with a firebrand in a dark night.”

Quote:

“It is necessary for you always to doubt yourself, rather than to hold a high opinion of yourself. Submit your ideas to men of learning and their writings. Proceed with caution, do not be hasty and avoid being vainglorious, for vainglory ends in a fall, and rashness causes one to make mistakes. He who has not turned his forehead to the gates of the learned will not become deeply rooted in excellence. Those who have not been put to shame will not be treated with respect by the people. Those who have not been reproached will not be shown the right way. He who has not suffered the pain of studying will not taste the joy of knowledge. He who has not worked hard will not become successful.”

Quote:

“Be sure to have death in view, for knowledge and piety are your provision for the world to come. When you want to disobey God, seek a place where he cannot see you. Know that men are the eyes of God with which he looks at His servants. He shows them a man’s good deeds, even if he hides them, and reveals his evil deeds, even if he conceals them; for his inmost soul is exposed to God and God exposes it to His servants. See to it that you make your inner [life] better than your exterior and that your secret [acts] become clearer than the acts that you perform in public.”

Quote:

“Do not become proud to the point of becoming unbearable, and do not lower yourself to the point of being seen as unworthy and looked down upon.”

Quote:

“It behooves a man to read histories, to acquaint himself with the biographies and experiences of nations, so that he becomes thereby, as one who, in this short life, has yet caught up with vanished peoples, has been their contemporary and companion and knows all the good and evil of them.”

-Abd al-Latif al-Baghdadi

Hello, and welcome. My name is Devon, and this is Human Circus: Journeys in the Medieval World, the history podcast that that follows that world’s travellers, a history podcast that is supported by a Patreon, where you can hear episodes a day early, with zero advertising, and with extra mini episodes, and you can do so on a pay what you’d like basis at patreon.com/humancircus. Thank you all of you have already done so.

And now, to the story. To the story of 'Abd al-Latif al-Baghdadi, and the story of one of his texts: The Book of Edification and Admonition: Things Eye-Witnessed and Events Personally Observed in the Land of Egypt. A book published last year in a new translation by Tim Mackintosh-Smith under the title A Physician on the Nile: A Description of Egypt and Journal of the Famine Years. ‘Abd al-Latif is someone I’ve talked about before in a Patreon bonus episode, but his work really justifies the full series treatment. Here, I’ll be talking about the context of that work, and by context I mean the life of ‘Abd al-Latif himself, his studies and travels. That will be our subject today.

For some of the sources on this podcast, their lives are fairly obscure to us, for some, as was the case for the subject of the last Patreon bonus, Wulfstan, completely so. We know of them only what crumbs they may let fall in their writings or, at a greater removal, their words, recorded by another. Not so with ‘Abd al-Latif though. Of him, we know quite a bit.

In this, we have the work of another man of that time to thank: ibn Abi Usaybi’ah and his biographical dictionary of physicians, for that was what ‘Abd al-Latif was or would come to be known as, the term signifying a much broader intellectual interest than only the medical as it would now. Ibn Abi Usaybi’ah himself came from a family of physicians, ones who had served Salah ad-Din in Cairo and at the hospital in Damascus. Born in 1194 and growing up in Damascus, ibn Abi Usaybi’ah would study and practise medicine in both those cities, and he did not only know ‘Abd al-Latif by reputation, as a renowned scholar of the time. ‘Abd al-Latif was friends with his grandfather, the two having formed a bond when both lived in Egypt, and had instructed ibn Abi Usaybi’ah’s father and uncle in literature and the works of Aristotle. The text actually includes a letter that ibn Abi Usaybi’ah wrote to ‘Abd al-Latif, and some kind words that ‘Abd al-Latif wrote of ibn Abi Usaybi’ah, referring to him as the son of his son. There was a personal connection there, a close one, according to the writer, and we benefit from that connection.

Ibn Abi Usaybi’ah wrote the first version of Sources of Information on the Classes of Physicians in the 1240s, later returning to the work in the 1260s. The book, often given in English as History of Physicians, Lives of the Physicians, Classes of Physicians, or Biographical Encyclopedia of Physicians, sounds like the type of text that you would need to take some time with. Its 700 some-odd pages sprawling their first eight chapters, and in the words of Cecilia Martini Bonadeo, across “the development of medical science from its invention, through its Greek, Alexandrine, and Islamic tradition, to describe the medical profession in Abbasid Baghdad. In the ninth chapter he gives brief information on the translators and their patrons. The remaining six chapters are entirely devoted to the doctors of Iraq, Persia, India, Morocco, Spain, Egypt, and Syria,” their life, works, and selected sayings.

It’s absurdly expansive, an incredible undertaking that you can dip into yourself, should you be interested, via the open access BRILL edition. But of course, not all of those 700-ish pages concern us here. We will be going straight to chapter 15. That’s where we find ‘Abd al-Latif. That’s where we find “ʿAbd al-Laṭīf al-Baghdādī … the shaykh and distinguished authority” also known as ibn al-Labbād, the son of the feltmaker, which is curious. That certainly wasn’t his father’s profession.

‘Abd al-Latif’s family was from Mosul, but he, as the name we know him by would indicate, was born in Baghdad. His father had been considered an accomplished Quranic scholar, his paternal uncle an outstanding jurist. He himself was noteworthy for his writing, his mastery of literary style and grammar, theology, Aristotelian philosophy, and medicine. In character, ibn Abi Usaybi’ah described him as industrious, hard working, devoted, always at study or composition of some writing or other, or else in transcribing texts, his own or those of others.

“At times – may God have mercy upon him, [ibn Abi Usaybi’ah wrote] – he would go too far in his talk: he had a high opinion of himself and would find many shortcomings in the intellectuals of his time and in many of former times also. He frequently disparaged the learned men of Persia and their works, especially the distinguished Master Ibn Sīnā [or Avicenna] and people like him.”

On his last stay in Damascus, ibn Abi Usaybi’ah saw him as “an old man of fragile physique, of medium height, a good speaker, expressing himself very well; still, his written word was more impressive than his speech.” But before he reached that point, before he journeyed, wrote, and taught for years still and ended his life in Baghdad in 1231, he had much else to do.

Fortunately for us, ibn Abi Usaybi’ah did only note down his remembrances of the old man, his admitted shortcomings, his high opinion of himself, or his selected aphorisms, some of which I opened this episode with. He also included in his book a great deal of biographical material that he said had been written in ‘Abd al-Latif’s own hand, and that material is rich in detail. It’s an intellectual autobiography, highlighting the progression of his studies at least as he viewed and wanted to present it, the texts he examined, the teachers he learned from, the paths he started down that he later discarded as incorrect, and this is how it begins.

“I was born in the year 1162 in a house belonging to my grandfather, in a street called ‘Sweetmeats Alley’, and I was brought up under the care of the shaykh Abū l-Najīb, without knowing anything of pleasure or leisure.”

It’s a remarkable sentence really, perhaps not to its writer, but to me, 800 years later, seeing that line about “Sweetmeats Alley” where he lived without leisure, the sweet in question apparently being the term for a bread sweetened with honey. That industriousness that ibn Abi Usaybi’ah had noted had been hard earned. ‘Abd al-Latif had spent all his time in studies of the Hadith, the acts and words of Muhammad, and listening to the luminaries of Baghdad. Or rather, not all his time, for he also found time to learn calligraphy, and to memorize the Qur’an and classic works of poetry, jurisprudence, philology, and stories.

Even then, still young, he was sure of himself, perhaps too sure of himself some would say, and given to that arrogance which ibn Abi Usaybi’ah had noted. Sent to Baghdad’s leading teacher, with whom his father had been friends since they’d studied law together, he found that, quote, “...[the man] talked a lot of nonsense, and uttered many foolish words. I could not understand one bit of his continuous and considerable jabbering, even though his students apparently admired him for it.” And maybe this opinion was a fair one, but the way the order of events is presented in the text he doesn’t seem to have kept it to himself. “I loathe teaching young boys,” that teacher apparently announced, passing them on to one of his students to see to their education until they were older.

‘Abd al-Latif would find other teachers, ones who seem to have better suited him, and he gives us a bit of a picture of what his education looked like. With an old blind man who also taught the vizier’s children, he studied from morning until the end of the day as part of a study group at a mosque, discussing various commentaries and reciting lessons. Then he would walk back to that teacher’s home, the old man helping him memorize what he’d learned as they went. Once there, his teacher would bring out the books he himself was working on, and they would go over them together. Then they would go to another man’s home, where the old man would give him lessons while ‘Abd al-Latif listened. It was a full day, and soon, our subject claimed, he was outpacing his teacher in powers of memory and understanding, that “high opinion of himself” again in evidence, though it may of course have been accurate.

There were other teachers, other sources of inspiration, other significant texts, some of which ‘Abd al-Latif credited for his development, some he decried as misdirections, particularly a book on alchemy, “the frivolous and idle experiments of error.” He listed this and that text and the time it had taken to learn them by heart. Eventually, he felt he had exhausted all that could be offered to him by the city of Baghdad, and in 1189, at about 27 years old, ‘Abd al-Latif went elsewhere.

He went first to Mosul, but that would not satisfy him either. He was there a year, finding students, taking up a position in “the second-storey law college of Ibn Muhājir and the Dār al-Ḥadīth on the ground floor below,” and apparently celebrated for his “expansive and rapid memory, quickness of wit and seriousness.” He recounted the works that he studied and memorized a portion per day, that he first read commentaries on and then wrote them. However, he was not impressed. Of one man, an expert in math and law, ‘Abd al-Latif would say that “His love of alchemy and its practice had so drowned his intellect and his time that he attached no importance to anything else but that art.” Of the writings of a philosopher who many were taken with, he wrote “I realized that many of my explanatory remarks, with which I was not yet satisfied, were better than the arguments of this idiot.” He was evidently not one to hold back.

Things were better in Damascus, with ‘Abd al-Latif now listing off works he had himself produced rather than studied. The patronage of Salah ad-Din, sultan and founder of the Ayyubid Sultanate, had drawn together many minds there in the city, and ‘Abd al-Latif mentions several by name, including a vizier who was later executed and a grammarian who was fond of debate but even fonder of himself and generally found to be offensive. There was a man ‘Abd al-Latif had much admired in Baghdad, who he had described as having the air of a religious man and the look of a traveller, and who here had a great following, but now ‘Abd al-Latif thought him a disappointment who invested trivial matters with great importance. He was thought by many to be immensely educated but “in fact,” quote, “merely possessed strange and radical views.”

“I saw through him,” ‘Abd al-Latif wrote, “and found he was not the man I had imagined him to be. … One day I said to him: If you had devoted the time you have wasted in the pursuit of [alchemy] to some of the Islamic or rational sciences, today you would be without equal… . This … nonsense does not have the answers you seek.”

Having himself gone down the path of alchemy for a time, ‘Abd al-Latif seems to have had little patience for those who continued that way, and this particular man, who had once “filled [his] heart with a desire to know all the sciences,” he counted as an example, a cautionary case who soon took ill and then died. “The fortunate one is who is warned by the fate of another,” ‘Abd al-Latif wrote.

From Damascus, that intellectual centre so generously funded by Salah ad-Din, he next went to the camp of the Ayyubid sultan himself.

‘Abd al-Latif journeyed to Jerusalem, and then to Salah ad-Din’s camp outside Acre. The first person he spoke to there was Bahāʾ al-Dīn ibn Shaddād, the qāḍī al-ʿaskar or military judge, and here he had an advantage because the man already knew of ‘Abd al-Latif, knew him by reputation and was immediately pleased to see him. “Let us join ʿImād al-Dīn, the secretary,” he said.

In the next tent over, ʿImād al-Dīn was writing a letter in ornate script, without having made a draft ‘Abd al-Latif noted. ʿImād al-Dīn put him to the test, questioning him on matters of theology until he was content. “Come,” he then said, “let us go to call on al-Qāḍī al-Fāḍil.”

That honourific referred to the close counsellor and secretary of Salah ad-Din himself, and a hub of the Ayyubid intellectual world. When ‘Abd al-Latif saw him, he saw a, quote:

“...thin man, puny (with a relatively big head and a lively mind), [all skin and bones and heart] who was simultaneously writing and dictating; his face and his lips moved about in all sorts of expressions due to the intensity of his effort to pronounce the words correctly, as if he were writing with all of his limbs.”

Like the others, al-Qāḍī al-Fāḍil questioned his guest, on the Qur’an and other matters, all the while never stopping with his writing and dictating. Eventually, he also was satisfied.

“Return to Damascus,” he said, “for there you will be given a salary.”

But our friend did not want to go back to Damascus. He insisted on Egypt though al-Qāḍī al-Fāḍil cautioned him against it.

“The Sultan is worried about the capture of Acre by the Franks,” he said, “and the killing of the Muslims in that town.”

But for ‘Abd al-Latif, it absolutely had to be Egypt, and al-Qāḍī al-Fāḍil relented, providing him with a short letter of introduction.

After this short break, we shall follow him to Egypt.

…

When ‘Abd al-Latif arrived in Cairo, he was met by al-Qāḍī al-Fāḍil’s agent in the city, “an old man of great virtue and authority,” and a noted poet and author. ‘Abd al-Latif was well cared for, provided with a well furnished home, money, and a grain allowance. He was introduced to all the proper people as a guest of al-Qāḍī al-Fāḍil, and was then showered with further gifts and blessings. And al-Qāḍī al-Fāḍil did not just forget about him after that. Every ten days, a letter would arrive in Cairo concerning governmental matters and there among them instructions as to the situation of ‘Abd al-Latif, who was left free to study, to write, to teach, and to seek out three men in particular.

The first of these was a disappointment. He found him them to be no better than “a swindler, a liar, and a common juggler.”

“It was said of him that he was able to do things that even [Moses] was unable to do,” summarized ‘Abd al-Latif, “that he could produce minted gold whenever he wished, of any quantity he wished, and in any coinage that he wished, and that he could turn the waters of the Nile into a tent, under which he and his companions would be able to sit; yet he was in a sorry state.”

He was so often disappointed by people, and so it was, to a lesser extent, with the second man who he had very much wanted to meet.

This one was none other than Moses ben Maimon or Maimonidies, and ‘Abd al-Latif admittedly did find him “extremely learned,” but then he also described him as being a bit of a bootlicker really, a man who was, quote, “overcome with the adulation of authority and service to those who occupied important positions.” And if that wasn’t enough to put ‘Abd al-Latif off, there was his opinion of one of Maimonides’ works being an “evil book that corrupted the foundations of law and faith.”

As for the third man ‘Abd al-Latif had hoped to meet, he would not disappoint but on initial impressions would not exactly inspire either. He first appeared to ‘Abd al-Latif as an old man at the mosque, shabbily dressed but pleasing in appearance and clearly held in awe by the others. It was only later on that day that the imam spoke of him to ‘Abd al-Latif, saying “Do you know this old man?” And then he said the man’s name. It was the very person our subject had wanted to see, and that’s what ‘Abd al-Latif told the man, embracing him and crying out “It is you I seek!”

He would later write of the man that “His speech and his doubts remained in my heart like something which gnaws away inside.” That day in Cairo, he brought the man back to his house for food and conversation and then would often after keep his company, arguing philosophy and, though he would not admit to submitting in those arguments, seeming to lean a little toward taking the man’s position in areas over which he had disagreed. In particular, this encounter seems to have marked the beginning of a move away from his attachment to ibn Sina, that “distinguished master” who, among others, his biographer mentioned him disparaging, the 10th-century born scholar who ‘Abd al-Latif had previously thought to hold all philosophy within him. Exposed in Cairo to this man’s knowledge of philosophy, of the ancients, he began to soften in that stance.

It was around this point that news reached ‘Abd al-Latif of a truce between Salah ad-Din and his Frankish opponents, news that the sultan was now bound for Jerusalem, so in 1192, that’s where our subject went, bringing as many books of philosophy with him as he could. And Salah ad-Din definitely did not disappoint. Our traveller saw him as “a formidable king, who filled all eyes with respect and all hearts with love, who was approachable, tolerant and generous.”

‘Abd al-Latif describes first finding him in a meeting and being impressed with how closely the sultan listened to all, and how he took part so actively and intelligently in detailed discussion of the walls and trenches of Jerusalem, how he would later be seen actually carrying stones for that work on his own shoulder, heading out for the purpose before sunrise and only returning for midday prayer and a meal before putting in another shift. He was, ‘Abd al-Latif says, an example to “the whole population, poor and rich, strong and weak alike,” and if that wasn’t enough to endear him to his visitor, ‘Abd al-Latif also says that the sultan provided him with a monthly salary that Salah ad-Din’s sons then added to with their own sums, the total a very comfortable amount, “ten times the usual stipend of a professor of law,” according to Mackintosh-Smith.

‘Abd al-Latif went back to Damascus then, settling into studies and teaching at a mosque there. He absorbed himself in the works of ancient philosophers and turned further away from those of ibn Sena, and he turned further away from alchemy too, which is a bit surprising. He had decried the dangerous lure of alchemy before, but of course that was all written in retrospect, after the fact. As much as he seemed to speak so strongly against alchemy at earlier points in his journey, that did not necessarily reflect where he actually had been at that point, maybe more a reflection of how he later looked back at that period in his life. It seems that a fair portion of his later distaste was driven by the pull that the art had held on him.

“I began to realize the vanity of alchemy,” he wrote, “and to know the truth of the matter about its foundation, its founders, and their lies and motivations. I was thus delivered from two great, ruinous errors. My thanks to God were redoubled on that account, for many people have been led to perdition through the books of Ibn Sīnā and alchemy.”

And Salah ad-Din was in Damascus too, but not for long. He was there and then gone to greet the pilgrims departing for Mecca, but on his return he was feverish and sick. Someone bled him then, someone without skill, ‘Abd al-Latif said, and the Ayyubid sultan soon weakened and died. It was the spring of 1193.

“The people were as afflicted with grief as if he had been a prophet,” ‘Abd al-Latif wrote. “I have never seen a ruler whose death so saddened the people; for he was loved by the pious and the profligate alike, by Muslims and infidels.”

The Ayyubid Sultanate fell into strife after that, something which I covered elsewhere on the podcast, and ‘Abd al-Latif stayed on in Damascus for a time, drawing a salary from its treasury even as one Ayyubid son besieged another, and then he was back to Cairo where one of those sons then ruled. He would lecture there at the al-Azhar mosque in the morning and then at midday teach medicine and other topics. Evenings were for his own studies.

This stay in Cairo was to some extent defined by death, some personal and close to him, some less so. There was Abū l-Qāsim, from whom he was inseparable, until his friend fell ill with a lung condition. ‘Abd al-Latif urged him to take medication, but the man, close to death, only replied with a line of 8th-century poetry: “A wound cannot hurt a dead man.”

There was Al-Aziz Uthman, Salah ad-Din’s second son, who ‘Abd al-Latif described as “generous, courageous young man, modest and unable to say no,” and for whom he wrote at least one book. He died in 1198, and soon after that, so did many others.

Though there’s no mention of it in ‘Abd al-Latif’s autobiographical material that was included, ibn Abi Usaybi’ah would have something to say about this period as that in which “Egypt was then visited by a huge rise in [food] prices and many deaths such as never had been seen before. The shaykh [‘Abd al-Latif] wrote a book on this subject, in which he described things that he had seen himself or heard from eyewitnesses, which make the mind reel.” That’s a little preview of the book we’ll be getting into next time, but we’ll put that aside for now.

‘Abd al-Latif wrote about Egypt in Egypt, compiling a work of Egyptian history and then writing his more immediate observations of the disaster as it unfolded. Then, in 1204, he moved to Jerusalem.

He stayed there for a while, ibn Abi Usaybi’ah would say, spending time at the al-Aqsā mosque where he wrote and taught, before moving back to Damascus in 1207. Again, he had no shortage of pupils, and again he worked on his own compositions. According to ibn Abi Usaybi’ah, it was at this period that he earned renown as an expert in medicine, which I found interesting, as I’d always thought of him as a physician first and foremost. But up to this point his reputation was apparently much more as a master of the “science of grammar.” I’ve elsewhere read something of an origin story for his shift in interest toward medicine that it came after he successfully diagnosed and treated himself using a 10th-century text.

‘Abd al-Latif was 45 when he arrived in Damascus and had clearly made a name for himself, as a scholar, as a physician, a master of grammar, and so on, and he would stay there for some time, but he would not settle and stay indefinitely.

He was in Aleppo next, and then, after that, travelling into Anatolia, where he would receive “important status … a large salary and many allowances” in the service of the governor of Erzincan to whom he dedicated his writings of that period. He seems often to have been on the move. You might wonder if he was not content, or if he was driven by his studies, going where the resources were or maybe the work. Though he doesn’t seem to have had trouble securing income, he may have had to keep moving to come by it, ever seeking the next patron. The instability of the post-Salah ad-Din years likely had a lot to do with that, and it has convincingly been argued that while his earlier travels tended to be in search of mentors, books, and teachers, his later ones would be in search of money, and of patrons.

That patron governor having been deposed, ‘Abd al-Latif was in Erzerum in mid-October 1228 and then in January of the next year back in Erzincan. February found him in Kamākh and April in Divriği, June in Malatya and August heading back to Aleppo, finding it greatly increased in prosperity and population, and finding, as he tended to manage to do, another patron.

There he would stay for a time, teaching medicine and other sciences along with language, listening to lectures at the mosque, and writing, always writing. Ibn Abi Usaybi’ah hoped to meet him there, but it would not work out. Still, he received letters and books from him.

After that, ‘Abd al-Latif went to Baghdad for the first time in a long time, the first in 45 years according to the text. He was planning on making the pilgrimage to Mecca and to stop in his birth city to offer some of his writings in tribute to the caliph, perhaps, it has been argued, seeking work at the college that ruler was then having constructed. But he would not travel beyond that. Indeed, it’s not known that he reached his audience with the caliph at all. In November of 1231, having at least arrived in the city, he fell sick and then died.

‘Abd al-Latif was not kindly remembered by all his contemporaries. One, whose friend ‘Abd al-Latif had admittedly referred to as a “damned devil,” dismissed his, quote, “pretensions to learning … like a blind man groping his way but claiming to be short-sighted,” and nick-named him something which translates to “Frying Pan Man,” which is, presumably, also not complimentary. From ‘Abd al-Latif’s fairly brutal assessments of others’ intellectual qualities, you could see how he might have rubbed a few people the wrong way. I like Mackintosh-Smith’s characterization of him as a, quote, “sometimes spiky character, but with an acute, humane, and ever-curious mind, one that probed a vast body of interests.”

Ibn Abi Usaybi’ah closes his entry on ‘Abd al-Latif with a list of 169 compositions by his subject, works varying greatly in size and subject matter. On Wheat. On Wine and Grapes. On the Determination of the Dosages of Drugs. The Stairs Towards the Goal of Being Human. On Thirst. On Water. And included on the list was the work we will be diving into next episode.

If you are listening on the Patreon, I’ll be back soon with the next bonus episode. If not, I’ll be back with the next episode on 'Abd al-Latif al-Baghdadi and his observations on Egypt.