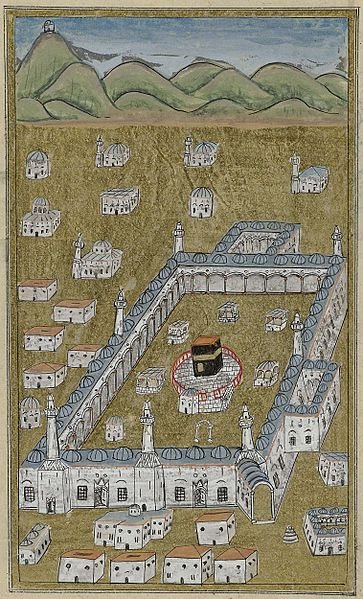

Anonymous 19th-century image of Mecca. (Wikimedia)

YOU CAN LISTEN TO THIS EPISODE HERE OR ON YOUR USUAL PODCAST APP.

Hello and welcome. My name is Devon, and this is Human Circus: Journeys in the Medieval World, the podcast that traverses that world through the stories of its travellers, and it is, as I never tire of telling you, a podcast that is supported by a Patreon. That means for as little as a dollar a month, or as much as works best for you, you can support me and my podcast while enjoying early, ad-free, and extra listening, sometimes more closely related to the main series, sometimes less so. Most recently on the extra front, we had a short story about family strife, curses, and exorcism. If you’d like to have that extra medieval listening and help support the podcast, you can do so at patreon.com/humancircus. Today, I want to especially thank Dave S. and Mary T.H. for doing so. Thank you both very much!

And now, back to the story.

As we have now left Prester John behind us, we are onto something new today, and yes, it has been quite a long time since that happened. So much so that I cannot easily remember what the series before Prester John was about without checking. I thought I’d do something shorter for a bit of a change, though this has not ended up being all that short despite my plans. This is another Medieval Lives episode.

The idea with these episodes is that they cover interesting medieval figures who, for one reason or another—lack of sources or lack of a longer story for example—I won’t be giving the full series treatment. This one falls into that category though it doesn’t quite fit the title of “medieval lives,” as it’s not actually about a life. The “figure” in question here is obscure to us, the author unknown, and not only obscured to us, for they likely obscured their identity to those around them on their journey, likely achieved that journey by professing to be Muslim, perhaps doing as the Italian Ludovico di Varthema had done earlier in the same century in claiming to be a mamluk.

The source today is from the late 1500s, a little later than tends to be labelled “medieval,” but then I’ve covered more recent material before. The source is an anonymous record that was published in English in 1599, in Richard Hakluyt’s The Principal Navigations, Voyages, Traffiques & Discoveries of the English Nation, but contrary to the title, is thought to have been translated from Italian, and that’s actually all we know of the author, except for what they have to tell us.

They tell us of the movement of a great many people, a vast caravan departing from Cairo. They record a pilgrimage to Mecca, the Hajj, some of its ceremonies, and some of the practicalities of bringing it about. They tell us a little of the lore and tradition picked up along the way. They are not always especially sympathetic toward the people they encounter—that is as you might expect—but they seem much more so towards those people’s religion, toward Islam, its stories, ceremonies, and traditions, or at least, that is how I read it based on this translation.

In the Hakluyt text, we find all of this under the heading “A description of the yeerely voyage or pilgrimage of the Mahumitans, Turkes and Moores unto Mecca in Arabia.” We begin in Alexandria, double walled and high towered, its cisterns filled by the channelled inundations of the Nile, and as the author would incorrectly have it, the most ancient city in Africa. Our traveller seems not to have fancied it much in the state he found it in.

There was little, by his reckoning, to recommend the ancient. Not the little castle with its guard of 60 Ottoman janissaries, Egypt and Syria by then being under Ottoman rule. Not the unimportant pyramid within the city, not even the thick pillar of Pompey outside it, the name owing to a long running mistaken association with Pompey’s head or ashes, though the column had actually been raised in honour of Diocletian.

The main problem, our traveller wrote, was the air, the evil and corrupt air issuing forth from the hollow city underneath the city, the one of old, still there beneath the foundations of this one in which people now lived and worked. Beneath the water in a nearby port, the riches of the past were pulled from long-submerged sepulchres and the remnants of other buildings, their gems bound for Ottoman temples and palaces. New riches were being produced at the merchant houses, among them French, Venetian, and Genoese. Silted up waterways and a general decline in importance had not yet entirely taken their toll on the city.

Our anonymous Italian, if that was indeed who he was, for I have also seen mention of possible Portuguese connections, cast his eye next along the coast, his gaze settling on a castle here, a sand-filled port there, all in varying stages of decay, disuse, or disrepair. Not so with Rosetta though, not so with that place also known as Rashid and now best known to many for the stone that would be discovered there. Its flourishing would sit at the other end of the teeter-totter from Alexandria, and at this point seems to have been doing very well. Though a “little town without walls,” it was the site of much traffic and its inhabitants very rich, if, according the author, “naughty varlets and traitors.” Perhaps there was an unpleasant personal experience there.

He also mentions that this Rosetta was to become the new Mecca, the preferred destination of Muslim pilgrims should Mecca ever be unreachable to them. I’ve also seen this mentioned in another old book of European of travel, but there with the incorrect explanation that this was because Muhammad had been born in Rosetta, which does not fill me with confidence on the whole Rosetta-as-new-Mecca claim.

As for Damietta, the place which we visited during the Fifth Crusade episodes of the Prester John series and an important stronghold during that struggle, it was now found to be of only very little military strength but “large, delightful, and pleasant, abounding with gardens and fair fountains.” On the path away from the coast, from Alexandria to Cairo, the writer would say it was “two hundred miles, in which I [found] nothing worthy of memory.”

Cairo itself was a different matter.

With new housing sprawling outside its walls, it was a place of many peoples, of quote, “Christians, Armenians, [Ethiopians], Turks, Moors, Jews, Indians, Medians, Persians, Arabians and other sorts of people, which resort thither by reason of the great traffic.” From that traffic and trade went an annual tribute in gold to the Ottoman sultan, escorted by a host of horsemen and janissaries. From the wealth that had long flowed through the city, it was, quote, “adorned with many fair mosques rich, great, and of goodly and gorgeous building…,” its houses, very fair and “richly adorned with hangings wrought with gold.” It’s safe to say that this traveller was very complimentary of Cairo, particularly of the August festivities when the Nile’s waters would flood and boats laden with beautiful women would row to and fro, accompanied by much feasting, singing, and drinking. He was quite complimentary of those women, in all their perfumes, jewels, and beauty. Not so much, the men, who the writer described as “foul and hard favoured.”

Of the surrounding countryside, the pyramids get a mention of course, along with the mummified remains of ancient men that were pulled from them, daily according the source. So does the Sphinx, just its head and neck then peeking above the sands. And so do the crocodiles, the danger they posed, and the enchantment that was said to keep them from passing Cairo.

And all of this was all very interesting, but it wasn’t really the main focus of the text. This, or at least that portion of it published by Hakluyt—perhaps there was more—was all about pilgrimage, all about the journey to Mecca. From all directions, this journey was made, but this one would begin there in Cairo. That was where the caravan gathered and was prepared. That was where they observed Ramadan, what the text called “a kind of Lent,” and celebrated Eid al-Fitr, the feast marking its end. A few days later, they made ready to leave.

A great multitude had gathered, from “Asia, Greece, and Barbary,” the writer has it, though this was actually not the only gathering place for the Hajj, the other of most importance being at Damascus. Cairo was more likely to draw pilgrims from across North and Sub-Saharan Africa, and traditionally also al-Andalus, though this source is from following the forced conversion, rebellion, and expulsion of Muslims from Spain.

The pilgrims went, the writer said, for the sake of devotion, for business, or to pass the time. They moved two leagues from Cairo to a place beside a large pool that had been filled by the Nile, and it would need to be large, for the 40,000 camels and mules, for the 50,000 people who now awaited the captain of the caravan, the Amir al-Hajj.

He was chosen annually, I have elsewhere seen, though this text has it as every three years. He would have been given gold, to give to the needy and for the needs of the caravan, and four hundred soldiers to protect it, along with six pieces of artillery, the latter’s purpose as much to roar in triumph and celebration as to intimidate. His officers were to see to the orderly movement of this great mass of people, his team of guides, its navigation. By night they would follow the stars, leading the way with lit torches, beaten on the soles of their feet if they ever should lead their many charges astray. With the caravan, would go merchants, sellers of tin, silk, coral, and grains, some of it to be sold on the journey, some at their destination, all of it avoiding the customs that would have been paid to transport the goods by sea.

Before the caravan’s departure, the Amir al-Hajj would have been to the castle in Cairo, presenting himself to the pasha. He and his officers would each have received a garment, his own in gold. They would receive for the kaaba in Mecca, a new gate worked all in gold, and the silk kiswah, the cloth to be laid over the kaaba with the shahada there in golden lettering: There is no God but Allah, and Muhammed is his messenger.” They would receive a cloth of green velvet and other ornaments to adorn the prophet’s tomb in Medina. The Amir al-Hajj and his officers would then depart, parading through the city with its people shouting and singing out, and, the traveller wrote, “a thousand other ceremonies too long to recite.” Out through the Bab al-Nasr they went, through that gate to the mosque outside for more ceremonies. They were not yet ready to leave.

All of this would already have happened by the time the pilgrims gathered at that place outside the city. After visiting the mosque, the Amir al-Hajj would stay in Cairo for another 20 days before going to the gathering place himself. There, he’d set his tent for 10 days, while the last of the pilgrims arrived. On the tenth, there’d be festivities, and the author would write of how the women and their camels would be so festooned with decorative tassels and knots that one could not see them without smiling. There’d be feasting and fireworks that final night before departure, along with volleys from those artillery pieces. Then at dawn the next morning, a trumpet would sound, and the great journey would begin.

It was only 40 days from Cairo to Mecca, but they were not quick and easy ones. You were on the march from two in the morning until sunup, allowed to rest until noon, and then would be marching straight on until nightfall, ready to be up again at two to start the day all over again. The only breaks from this punishing schedule were water sources where, by necessity, the travellers and their animals would be given water and respite. It was to be a hard journey, but that didn’t mean it had to be fatal.

At the front of the caravan went 8 guides or pilots. With them went an officer and 4 men with bull sinews to whip them with if their guidance was untrue, and 6 clerics who would sing out the good news when they reached a place of rest. Just behind them, came about a third of the entire caravan, along with 25 camel-riding cavalry, armed with sword and bow against thieves. It was very few to protect so many people, but then I suppose they were more like armed event security than an invading army.

About a quarter of a mile behind them, came the six artillery pieces with their gunners and a squad of archers. There too could be found the caravan’s chief physician, with spare camels for the unmounted sick to ride, and there also was the fairest camel that could be found, draped in golden cloth and silk, accompanied by singers and musicians, and carrying an unadorned chest holding the Qur’an. The chest would be simply covered in silk during the journey, but for the entrances into Mecca and Medina would be dressed in gold cloth and jewels. In that same section of the caravan were camels carrying vestments, and ones with the money and provisions of the Amir al-Hajj. With it went many others who journeyed to Mecca, along with another 25 archers and an officer.

To their rear, always within a mile, went the bulk of the pilgrims themselves. While the merchants would prefer to be further forward for the security of their goods, these were pilgrims who had little of value they feared losing, and they were not totally unprotected. An officer went behind them with 40 archers and 25 cavalry.

This great caravan, complete with steeds, provisions and goods, stretched out south by southeast along the bank of the Red Sea, their eastern flank unprotected by water, patrolled by 200 janissaries. All through the line, on this side or that, went the Amir al-Hajj, everywhere accompanied by his own guard of an officer and 25 armed men on camels, along with 8 musicians who played for him every hour he was not at rest, making known his presence as he moved about among the people.

As the caravan travelled, one of the Amir al-Hajj’s responsibilities, one of the reasons he needed to be so well-funded, was to spend money on safety and security. Much as we’ve seen in other episodes from time to time, this world before the borders we’re familiar with today was not necessarily because of that one in which you could simply travel freely. There were fees involved in moving goods and people about, sometimes at a fixed and commonly understood rate, something we might understand as official, sometimes more a matter of negotiating with this local lord or that.

That was what the Amir al-Hajj now did, exchanging gifts, garments, and money with this or that Arabian lord or Bedouin group in return for safe passage and services, a duty that purchased security from thieves, and the promise that what was nonetheless taken on this land would be repaid. For all those efforts, there would still be uncompensated theft. No one could entirely guarantee against that, and this was of course such a target drifting across the landscape. Sometimes, our traveller wrote, the only restitution victims would receive was “the sight of [the thieves’] heels as they [flew] into places where it [was] impossible to find them.” This mass of pilgrims, merchants, officials, and wealth moving across their land represented too rich a resource not to be tapped, but that relationship went both ways as locals were relied on for food, mounts, and access to water. So it had been for some time, and so it would be for centuries still, as future travellers would attest to.

It was all a delicate balance. Caravan commanders and intermediaries might seek to skim profits off the payments, and there was the question who got how much, the more powerful and aggressive groups requiring a greater payment to keep peace in their interests, those with other troubles or less power, not so much. There must have been some experimentation in finding just the right amounts, and the Bedouin would have had their own calculations to make in all of this.

Entering the territory of the Sharif of Mecca, the caravan would be received with great joy and there would rest for a day with access to plentiful water, dates, and meat, mostly sheep. Travelling on, there was a place where they would cross a large field, with mountains to their side. On that site, Muhammad was said to have won a great battle with angelic support, and as they passed it, a drum would sound from the mountain, said to be beaten by an angel. There was a place where balm would grow, where the pilgrims would wash their bodies and put on simple garb. Though the author did not know it as such, they were entering ihram, the sacred state necessary to make the pilgrimage.

Coming within two miles of Mecca, the caravan would halt for the night. Then, with much celebration and ceremony, in the morning they would approach. The order of things that followed would not necessarily follow those of the Hajj, perhaps an error of the writer, but perhaps more likely one of translation or transcription. After this quick break and a word from fellow history podcast, Historical Blindness, we’ll see how it is presented in that 16th-century text.

…

The sharif and his guard would come to meet the pilgrims with an “infinite number of people.” They would go to nearby grounds where tents had been set, in their centre a pavilion for the Amir al-Hajj himself. There, that amir would give rich gifts to the sharif, of cloth, gold, and jewels, and the sharif in turn would turn over to the amir his authority, his power to govern there in Mecca for the length of the pilgrims’ stay. Then they would sit and eat together. After that, they and few others would go to the kaaba to install the new gate and place the kiswah that had been brought from Cairo. The cloth that had previously been in place was removed and taken to the mosque to be cut to pieces and sold to pilgrims, the relics said to among other things clean away the sins of those who were about to die.

The author describes Mecca there among “exceedingly high and barren mountains,” describes the plain between Mecca and the mountains with its pleasant gardens, its “abundance of figs, grapes, apples, and melons,” the matching “great abundance of good water and meat, but not of bread.” The city itself is without walls and about 5 miles round, its houses “very handsome and commodious, and are built like the houses of Italy. The palace of the Sharif is sumptuous and gorgeously adorned.” But as in Cairo, there was, unsurprisingly, a more judgemental tone as to the actual people, the women being “lovely, fair, with alluring eyes,” but men and women alike written of as given to that quote, “abominable, cursed, and opprobrious vice” of thinking themselves cleaned of sin, having washed themselves, although, quote, “like the dog they return to their vomit.” Along similar lines, the crowding of the city’s mosques is described as making it “worse sometimes than a den of thieves.”

And the city would indeed become crowded, not that this somehow converted the crowds to thieves. At the same time the caravan from Cairo arrived, others would also come, from Damascus and, the text rather vaguely says, Arabia. All who lived within ten days’ journey would come too, so that, by the author’s estimate, around 200,000 people and 300,000 animals might be found at that one time around Mecca.

At the centre of the city was that great mosque, with its pillars of marble, lime, and stone, its 95 gates, and its 5 towers from which the muezzin would call, the Masjid al-Haram like a cloister within which could be found the kaaba itself.

You will have seen that distinctive black stone cube structure, in art or in photos, or in person. In this Italian traveller’s description from before the early 17th-century reconstruction, it is “made of speckled stone, twenty paces high and forty paces in circuit.” There is a stone within the wall said to have fallen from heaven, and a voice heard to proclaim that “wherever the stone fell, there should be built the House of God.” It is written that the stone was not originally black but has become so from the kisses of so many sinners.

“The entrance into the House is very small, made in the manner of a window, and as high from the ground as a man can reach, so that it is difficult to enter… . There stand at the entrance two pillars of marble, one on each side. In the midst there are three [pillars] of aloeswood, not very thick and covered with tiles of India of one thousand colours… . It is so dark that they can hardly see within for want of light. Outside the gate five paces is the Well of Zamzam, the blessed well that the angel of the Lord showed to Hagar when she went seeking water for her son, Ishmael, to drink.”

From outside the city, the pilgrims enter. Guided in groups of 20 or 30, they ascend the street to the Bab al-Salam, the “Gate of Peace.” From there, the Masjid al-Haram is visible, and they greet it twice with the words, “Peace to thee, ambassador of God.”

Our writer shows them moving from arch to arch in prayer. Shows them saying the words said to have been uttered by Hagar in her search for water. Shows them circling the kaaba seven times and kissing the Black Stone. Shows them cleaning themselves at the Well of Zamzam. As they still would today. All who came on the Hajj would do this once, some every day that the caravan remained there.

Having, according to our author, been at Mecca for five days, all would gather, all from across the three caravans and those already living in proximity to the city, and would go from Mecca to the place where Eve and Adam were said to have been reunited after their expulsion, humanity’s “very first earthly home” as Jeffrey Einboden would write. To Mount Arafat, the “Mountain of Pardons” or “Mercy,” though in the text it is remarked that perhaps, on account of its size, “hill of mercy” would be more accurate. It is little, but “delightful, and pleasant, and containing in circuit two miles and surrounded with the goodliest plain that ever with man’s eyes could be seen.” Indeed, the text tells us, it was “one of the goodliest situations in the world,” for it seemed that “Nature [had] shown all her cunning there, in making the Mountain of Pardons so broad and pleasant.”

The night before there would have been celebrations by all three gathered hosts, with the mountain in their middle. There would have been “gunshot and fireworks of sundry sorts, with such singing, sounding, shouting, hallooing, rumours, feasting, and triumphing that it is wonderful.”

After all that celebration, the next day was a quieter one, given to rest, prayer, and offerings to God. That evening, all gathered as close to the mountain as they could. Then, in the place where Muhammad had given his Farewell Sermon, they listened, as s speaker ascended the steps to a pulpit, and a sermon was given, “a short sermon” the text tells us, but for all that, the author included a surprising amount of detail as to the material.

The speaker showed his audience all the good things that their God had done for them through the efforts of the prophet Muhammad who had rescued them from the sin in which they’d lived. How they’d been given the House of Ibrahim, the Kaaba, how they’d been given that Mountain of Mercy, to be heard and to be granted grace. He told them of how the mountains of the world had gathered at that place to create the mount, but that the little hill had been unable to pay its debt to them and was saddened. He told them of how God had, out of compassion, intervened, saying to the mountain:

“Weep no more my daughter… take comfort, for all those that go to the house of my friend Abraham will not be absolved from their sins, unless they first come to do you reverence and to keep their holiest feast in this place.”

Then the preacher exhorted them all, “to the love of God, to prayer, and to almsgiving,” and, with the sermon’s conclusion at sunset, the crowd prayed and then departed. There was much still for them to do.

There would be a fair at Mina where much business would be done, without customs or duties, and that night after the sermon at Arafat, they would gather rocks at Muzdalifah, taking them to Mina where they would hurl them at three stone pillars in the symbolic stoning of Satan. There would be the Tawaf, the seven circuits of the Kaaba, for despite the order of events as presented in the text, that would not take place before the day at Arafat.

In the text, you see the pilgrims then head towards home, or at least toward Cairo, but they don’t go straight there. Some lingered at the edges of the sharif’s territory, in that place where the balm grew, where they had stopped on their way in. Others would leave the coast. They’d turn inland and make for Medina. Drawing near enough to see “the city and tomb of Muhammad,” they dropped from their horses and shouted their prayers greeting. They would camp that night within three miles of the city.

There were a great many fountains and gardens around Medina, “infinite ponds, abundance of fruit.” A mile from the city was a house where Muhammad was said to have lived, and around it date trees said to have been grafted by his own hands, their fruit sent to the sultan. Near it, was a fountain of clear water that was piped into the city.

The Medina the pilgrims found, the Medina our traveller found, was “a little city of great antiquity, containing in circuit not above two miles, having therein but one castle, which is old and weak, guarded by an Aga with fifty pieces of artillery, but not very good.”

The houses, on the other hand, were “lime and stone,” “fair and well situated.” The mosque at Medina’s centre, Al-Masjid an-Nabawi or “The Prophet’s Mosque,” was, quote, “not so great as that of Mecca,” but perhaps only in size, for it was deemed “more goodly, rich, and sumptuous in building.” And at its corner was the tomb of the prophet, now very apparent beneath the Green Dome, but then not yet green. At that time it was described as “far exceeding in height the mosque, being covered with lead, and the top all enamelled with gold, with a half moon upon the top.” Below, attended on by fifty eunuchs, only three of whom could enter, was the body of the prophet Muhammad, his situation described in this way.

“...over the body they have built a tomb of speckled stone a brace and a half high, and over the same another of [timber] foursquare in manner of a pyramid. After this, round about the sepulchre there hangs a curtain of silk, which [restricts] the sight of those without, that they cannot see the sepulchre.”

Rather more contentious, is what the text has to say of those occupying the two sepulchres near to Muhammad’s. In our source, those are not the first two caliphs Abū Bakr and ‘Umar, who you’ll elsewhere read are there under the Green Dome. Those early caliphs were in this text located just outside the city, along with the third Rashidun caliph ‘Uthman, all visited by pilgrims but not so close to Muhammad. Next to him instead, it’s Muhammad’s cousin, the second to believe him after his wife, and the first Shia imam, Ali, and its Ali’s wife, Muhammad’s daughter, Fatimah, a very different framing as to who was buried alongside the prophet, and perhaps one indicative of who our author spoke to.

In Medina, the pilgrims would go to the mosque and the tomb, bringing decorative cloths and coverings, just as they had at Mecca. After that, the Amir al-Hajj would rest in Medina for two days while the pilgrims finished their devotions. Then, rejoining the others where they had left them, the return journey continued north.

There was a narrow place between two mountains that had once been called the “Iron Gate,” making it one of several passes by that name, this one said to have been created by Ali himself. The story went that Ali had been pursued by many Christians when he had come to that place, and with no route of escape, had struck at the mountain with his sword, dividing it in two and winning his safety. “Moreover,” the text goes on to say, again perhaps telling us something about who its author spoke with, “this Ali among the Persians is had in greater reverence than Muhammad, who affirm, that the said Ali has done greater things and more miraculous than Muhammad… .” I’m not sure exactly how precise the author was being here in their use of the designation Persians, the term, like “Turk,” sometimes getting flung around a bit indiscriminately by European authors of this period, and the text tells us no further about it, sharply segueing into the next sentence with the words “But to return to our matter…” as the pilgrims made their way home, the author finding little more to say.

Arriving at al-Birkah, the place where they’d initially gathered close to Cairo, they’d be met by a member of the pasha’s household and all his horsemen, and the Amir al-Hajj would enter Cairo. The pasha would receive him in “great joy and gladness” and would present him with a rich garment of gold, and the amir in turn would produce that qur’an which they had borne with them and return it to the pasha’s keeping. There it would remain for another year.

The Amir al-Hajj would be celebrated for his successful handling of the pilgrimage, would enjoy the prestige of victory in that campaign, that feat, and it was an equivalent one to a large military venture, the Ottoman budget for the Hajj estimated at a half or two thirds that of their war on the Habsburgs. Some of that effort went to infrastructure, to wells, roads, barracks, and the like, but it went also to directing this mobile city as it fulfilled its religious purpose and made a considerable statement as to the Ottoman sultan’s own legitimacy as ruler of the home of Islam. It was no small thing for it all to go well, and it had not always gone well.

The 1521 caravan had struggled home in difficult circumstances. One historian of the period, a man who undertook the Hajj the following year, wrote that quote:

“The pilgrims had suffered a great deal from a shortage of foodstuffs and the deaths of many camels. On their departure from Aqaba the cold had become intense and the wind blew with gale force. A large number of pilgrims died there: between Aqaba and the arrival in Cairo there were probably about 80 deaths. Others remained seriously ill because of the cold and the wind, which their bodies had not the strength to resist.”

As for our traveller, his journey seems to have gone much more easily than this, or so I would say from his lack of comment as to its return leg, and from there, he would disappear from the story. Some would say he’d never appeared to begin with.

I hope you enjoyed this episode. If you are listening on the Patreon feed, you’ll hear me back soon with some bonus listening. If not, I’ll be back soon after with the next main episode. Either way, thank you for listening. I’ll talk to you soon.