Giovanni Fontana was a 15th-century Italian engineer and inventor. His designs included everything from systems for retrieving sunken ships and automating the defence of fortifications to measuring time and producing music. He created locks, clocks, and magic lanterns.

If you like what you hear and want to chip in to support the podcast, my Patreon is here.

Here are some examples of Giovanni’s creations:

Sources:

Fontana, Giovanni. Bellicorum instrumentorum liber cum figuris... Digitized at https://codicon.digitale-sammlungen.de/inventiconCod.icon.%20242.html

Gilbert, Bennett. “The Dreams of an Inventor in 1420,” Public Domain Review. 2018. https://publicdomainreview.org/essay/the-dreams-of-an-inventor-in-1420/

Grafton, Anthony. “The Devil as Automaton: Giovanni Fontana and the Meanings of a Fifteenth-Century Machine,” in Genesis Redux: Essays in the History and Philosophy of Artificial Life, edited by Jessica Riskin. University of Chicago Press, 2007.

Grafton, Anthony. Magic and Technology in Early Modern Europe. Smithsonian Institution Libraries, 2005.

Grafton, Anthony. Magus: The Art of Magic from Faustus to Agrippa. Harvard University Press, 2023.

Rossi, Cesare and Russo, Flavio. Ancient Engineers' Inventions: Precursors of the Present. Springer, 2016.

Sparavigna, A.C. “Giovanni de la Fontana, Engineer and Magician.” Cornell University Library, 2013.

Script:

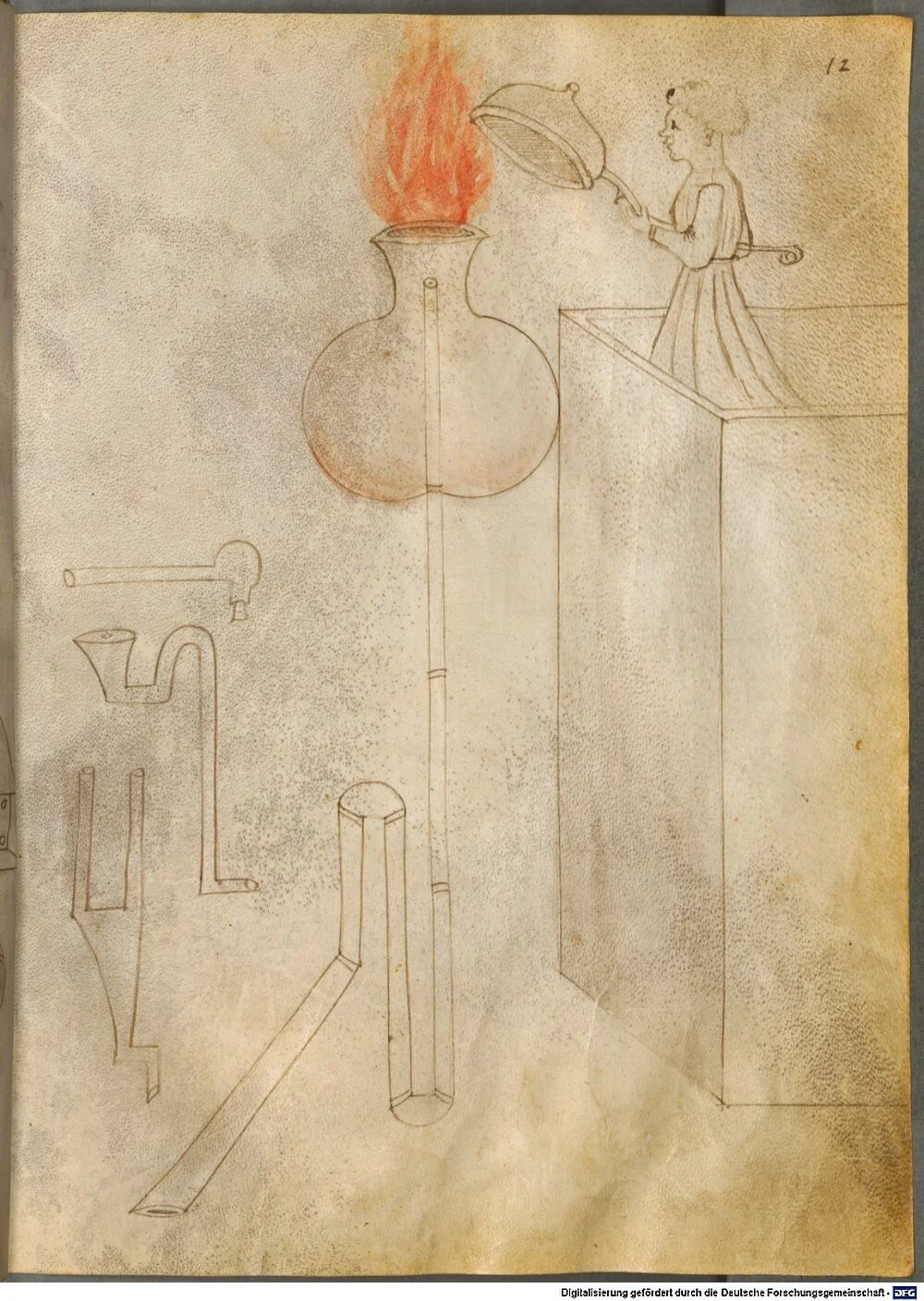

To quote the subject of today’s episode, “God has given humanity so much force of intellect, that they have devised many arts, and brought about many things that nature could not have done on her own.”

There are those things, he says, which:

“...the people call ingenia, many of which architects have attained with geometrical measures, physical arguments or arithmetical reasoning. For example, there is the screw, from which is derived the pump, which expels water in a spectacular way. And there are the multiple sets of pulleys, an extraordinary device through which ropes run, and which can pull or suspend incredible weights with a light pull. … There is also the terrible machine which we call the bombard, which destroys every form of resistance, even marble towers.”

As his words would indicate, today’s subject was concerned with brilliance, with mechanical ingenuity of all kinds, from the harnessing of water to the employment of weapons of large-scale destruction, sometimes both at the same time. He studied human anatomy, the recovery of sunken ships, and the nature of perspective. He wrote on apparitions in the sky, on mechanical demons, and on medical recipes. On locks, on clocks, on things that flap their wings and breathe fire.

Today, we’ll talk about him, and we’ll talk about one of his texts in particular.

Hello, and welcome. My name is Devon, and this is Human Circus: Journeys in the Medieval World, the history podcast which moves through that world in the footsteps of its travellers, and it is a podcast that is supported with a Patreon, one where you can help the podcast stay on the trail of those footsteps, ensure it never strays from the path of safety and into the surrounding desert, there to be lost until some future wanderer finds its bones alongside some sort of accompanying warning sign, proclaiming in crooked lettering: “Do not go here.” You can do that while enjoying extra listening, early listening, and blissfully advertising-free listening. You can do that for as little as a dollar a month, or as much as makes sense for you. You can do that at patreon.com/humancircus or via the link in the episode notes, and you can do that right now if you’re so inclined, and possibly finish the episode in a warm rush of good feelings, though I don’t want to go overboard and over promise here.

And now that you may or may not have done so, let’s get back to the story.

It’s another stand-alone episode today. There are longer series on the horizon, but something a little more self contained is what I’ve been feeling like, so today it’s another of my Medieval Lives episodes, where I tell the story of someone who, no matter how interesting I find them, doesn’t necessarily fill out a longer series, either due to the modest nature of their deeds or, much more likely, the maximum weight that the available sources will support.

Today, the life in question is that of Giovanni Fontana, a 15th-century physician and engineer and the creator of many intriguing books, including one, which has been preserved for us to view today, that is especially so.

Giovanni lived from about 1395 to around 1455, so the first lesson learned in researching him is simply not to mix him up with the 16th-century architect and mathematician of the same name. Our Giovanni Fontana was not the one put to work on the problems of flooding by Pope Clement VIII, not the one whose brother Domenico raised the Vatican Obelisk in St Peter’s Square in 1586. Nor, I suppose I should mention, was he the 1946-born Italian poet and artist. But this is not to say that our Giovanni achieved nothing himself. Indeed, his legacy was brilliant, if slightly peculiar.

Giovanni was born in Venice, with some saying it was 1395, others putting the date closer to 1390. He would write of remembering a dreadful event, thought to have been a 1410 Venice storm, and he would appear more concretely in documents relating to his presence at the University of Padua. Little is known about the early period of his life, but there at Padua, west of Venice, the facts are highly specific. He witnessed examinations there on May 26th, 1416. He took exams there on June 18th and 19th, 1418, at the bishop’s palace and then at the cathedral. He was given the degree of doctor of medicine on May 17th, 1421.

Like I said, the specifics are there, but it’s a little like looking at a drawing of a face, only they’ve just done two eyelashes and a single tooth. They’ve told you that Giovanni would work as a physician for some 20 years, that he made the acquaintance of the Count of Carmagnola, to whom he delivered a message from the Venetian doge, and that he was in Udine, in northeastern Italy, in 1440. That he likely wrote his last book some time between the 1450 church jubilee, which he mentioned there in his writing, and 1454. That he went to Rome at some point in this period, and Crete. That he died some time after 1454, the exact date and place unknown.

In between those vague dates of 1390-something and 1454ish, Giovanni was not just a physician. The work he produced which would really draw interest, or at least my interest, was that of an engineer, and at times quite a speculative one.

You see some of his work in the nature of the texts that have come down to us, sometimes only as fragments or mentions of works that had once existed, ones that may, I suppose, still exist again, should they resurface. It’s not impossible.

In his first treatise, Giovanni wrote of the clepsydra, the Greek word for a type of water clock literally meaning “water thief,” which I find quite enjoyable. In his second, he returned to the water clock and to other methods of measuring time making use of the elements. He wrote the rather misleadingly titled Treatise on the Fish, the Dog, and the Bird, apparently a combination of magical illusions with mechanical experiments. He also returned to measurements, to time as assessed through the burning of candles or oil, or by the movement of wheels. To unknown heights or depths evaluated through the dropping of objects. He also brought up tales of Alexander and others, of flight or descent into the water. He wrote a treatise on perspective and presented it to the painter Jacopo Bellini, something which I can only imagine delighted the painter, as few people don’t enjoy being lectured on their area of expertise.

At some point around 1430, Giovanni wrote a work on memory, on different types of memory, and on various mnemonic techniques. The text is encrypted but in a way that was, quote, “established on the basis of a symbolic view of signs, and therefore used not to conceal the text but to enhance the mnemonic mechanism.” He wrote on the construction and application of the sextant in order to collect dependable geographical data. He wrote an encyclopedic text that took in everything from the regions of the Earth and their flora and fauna, to the celestial influences and how they did not outweigh the human will which remained, at least in part, free.

He also spoke a little of magic, something you might not expect from him.

As Anthony Grafton notes, “in 15th-century Italy, the making of statues that moved could smack of more than technical ingenuity,” and our Giovanni was certainly someone who dealt in statues that moved, or at least he was someone who drew and designed them. And he did not entirely shy away from the world of what one might call the arcane.

In that book on memory, he alluded to the knowledge that might be gained from the inspiration of angels and demons, and he himself claimed to have gained information from a “spiritual substance,” whatever you take that to mean. He spoke of, quote, “...the spirits, that, once impressed on the idols of the pagans, they gave answers, and lured the pagans to idolatry.” He was concerned about certain “magi and necromancers” making use of holy characters and angelic names to trap these spirits in statues or bodies.

Mostly though, he seems to have opposed supernatural explanations when there were others at hand through experimentation and observation. He writes, for example, of reports passed on to him by his former teacher, of sightings in the sky and their interpretation.

Quote:

“...in the year of grace 1403, horsemen and footmen armed with lances and swords appeared, attacking one another, in the clouds every day for three days, before the third hour, in Lombardy, near the town called Busseto. Those who saw this were terrified, not knowing the cause of this novelty.”

And fair enough. It was the sort of vision that would indeed surely terrify and confuse, and it’s not the first time we’ve come across such testimony on this podcast. A report in ibn Fadlan comes to mind, if I am not misremembering. But in this case at least, Giovanni believed that he knew better. He was no simpleton, to be so easily taken in and caused to panic. He had his own explanation, if one that may not entirely satisfy us now.

It was only that the Duke of Milan had assembled an army for the purpose of besieging Bologna in a nearby plain, he argued. It was only that a particularly watery cloud sat just so in the sky, so that it might, quote, “accept a likeness of the armed men in motion.” It was this mirroring likeness that was seen by the people, leading them to believe that “there were demons in the air, fighting, with the appearance of armed men, … either voluntarily or by the art of magic.” You may or may not find this more compelling than the original reports of demonic armies in the sky.

In another example, Giovanni wrote that, quote:

“...in the city of Milan, several images like angels were seen. Some of them seemed to be trying to come down to earth, and some to climb to heaven. Some had trumpets and some had swords in their hands. Everyone was terrified of these visions, as if God wished to hasten the last judgment.”

However, he claimed, the actual reason was significantly less alarming. It was just that a statue of an angel, sword and trumpet in hand, was atop the peak of a somewhat nearby tower, and that this statue, quote, “presented [it]self to the aforesaid watery cloud as to a mirror. The images were multiplied by the motion of the cloud, as if in moving water, and seemed to move in various ways,” creating the wonderful effect of angels rushing both heaven and Earth-ward.

I must say that I rather wish clouds would reflect images of Earth in such a manner, though I suppose we wouldn’t often get mounted armies and angels. It’d be more like cities in the sky for most of us, which I’m not really opposed to either, but maybe if the clouds sat just right, you’d get a multitude of bears crashing across the sunset or something similar. It sounds nice.

But of course, for Giovanni’s contemporaries, it generally wasn’t. It was, understandably enough, horrifyingly ominous, all these angels and armies, the cause of panics, pamphlets of alarm, and rumours leading to political strife. “Cause,” for Giovanni, was the key word. It was “ignorance of the cause” in particular that led to this unrest, to fear, and unnecessarily so. As far as he was concerned, a student—perhaps he would have said “master”—of optics and perspective such as himself, could reliably recreate any such phenomena “by art, and not even a magical one,” he said, “but by pure craft.” He could also confidently refute any charges of demonic power or witchcraft behind his works.

Maybe, as Grafton suggests, this was why so many of his drawings, his designs, were, one might say, unnecessarily provocative. Did an automaton strictly need to take on the form of a fire-breathing witch? Did his “magic lantern,” which we’ll touch on later, need to use the image of a fearsome demon? Perhaps not, but it may well have been sparked by accusations from some in Padua that there indeed were secret seals and “infernal spirits” behind his work. In depicting such things, to quote Grafton, Giovanni:

“Again and again … wrapped his purely mechanical devices in frightening exteriors that recalled the other great set of 15th-century claims to human power over nature, those of the magician. By doing so, he suggested that engineers could claim the same immense powers as magi. By the same token, and more radically, he mechanized the apparently preternatural or supernatural—and by showing that he could do so, he exalted his own craft as no one before him had.”

Let’s turn now to the book in which he did so much of that, but first, a quick break.

…

The book that I especially want to talk about today is one that I will post examples from, including the ones I’ll talk about here, on the podcast website, and I’ll link that in the episode notes if you want to have a look for yourself. It’s the one known, in Latin, as “The Illustrated and Encrypted Book of War Instruments,” but that was not all it was, not even mostly what it was. It was a work that focused on his illustrated designs for mechanical and hydraulic devices, some of them, clearly, constructs for application in warfare, others for transportation, manipulation of light, or the making of music.

From the ancient world, the book would reference Philo of Byzantium, the 3rd-century engineer who lived in Alexandria and wrote on everything from leverage to siegecraft, the writer sometimes credited with a treatise on the seven wonders of the world, though it’s possible that its author was quite another Philo. It would reference another Alexandrian Greek named Heron, a writer on mathematics and on devices that harnessed wind and steam.

Of early medieval sources, it would make use of Isidore of Seville and of al-Kindi, the Baghdad educated polymath with an absurdly abundant written body of work, sprawling into philosophy, astrology, optics, anatomy, medicine, music, cryptography, and more.

Of more contemporary ones, there was the English theologian and physicist Thomas Bradwardine and the 14th-century French philosopher Nicole Oresme, a writer on everything from cosmology to economics and a translator of Aristotle into Middle French.

Featuring about 70 illustrations of sundry appearance and application, the book forms a kind of portfolio, a sampling cross section of all Giovanni was capable of. And some have seen its purpose as akin to that of a portfolio. This is what I am capable of, they have him saying. This is what I can make. Wouldn’t you like to give me some money to do so for you?

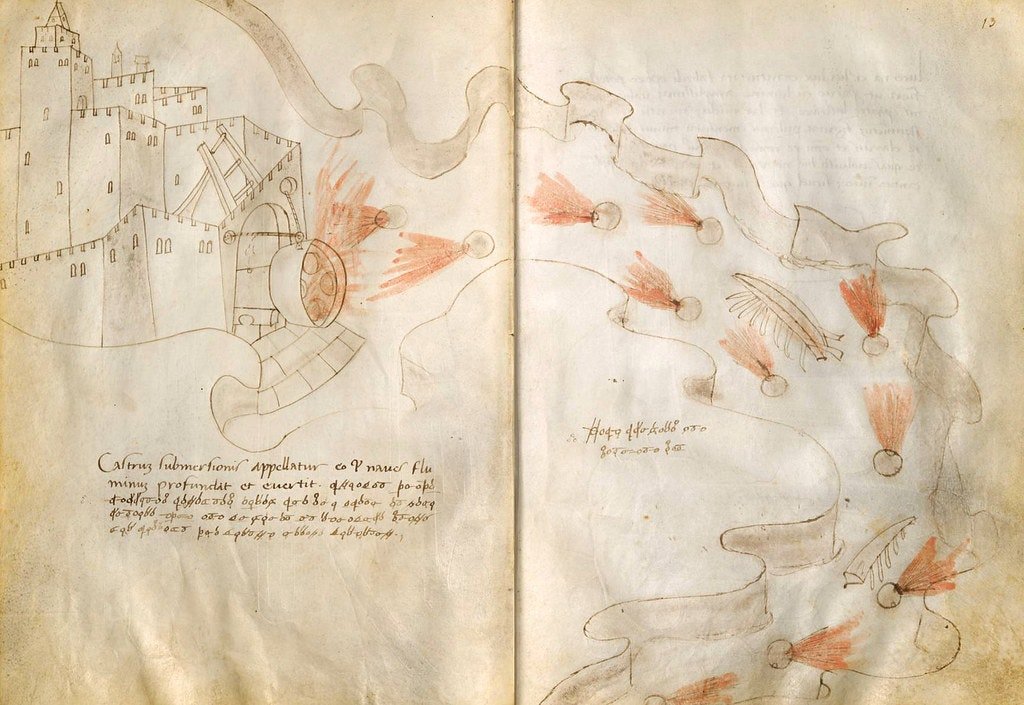

Some of what was illustrated in the text was indeed applicable in times of war. You can turn to one page and find a castle illustrated on the left. It’s pleasingly inexact in its lines, the tops of its walls wobbling along at this angle or that, but it communicates the idea of “castle” well enough, and there’s something else that is unusual about it. Jutting from the gate, you see an enormous device, a kind of gaping cannon, big enough to fill the bulk of that opening and displaying four exit holes, like a kind of oversized, four-barrelled gatling gun. The whole apparatus is shooting a barrage of fire-driven spheres that follow the water-course outside the castle’s walls like large round torpedoes, perhaps the sort of torpedo that certain people in Padua would accuse him of involving diabolical powers to propel.

You turn to another page, and it’s a siege engine, an appliance for hurling death most efficiently at one’s enemies, or at least that’s very much what it appears to be, though perhaps it had some more innocent purpose to serve. I am, I’m not embarrassed to admit, hindered by my inability to read the encrypted explanations of this 15th-century Italian.

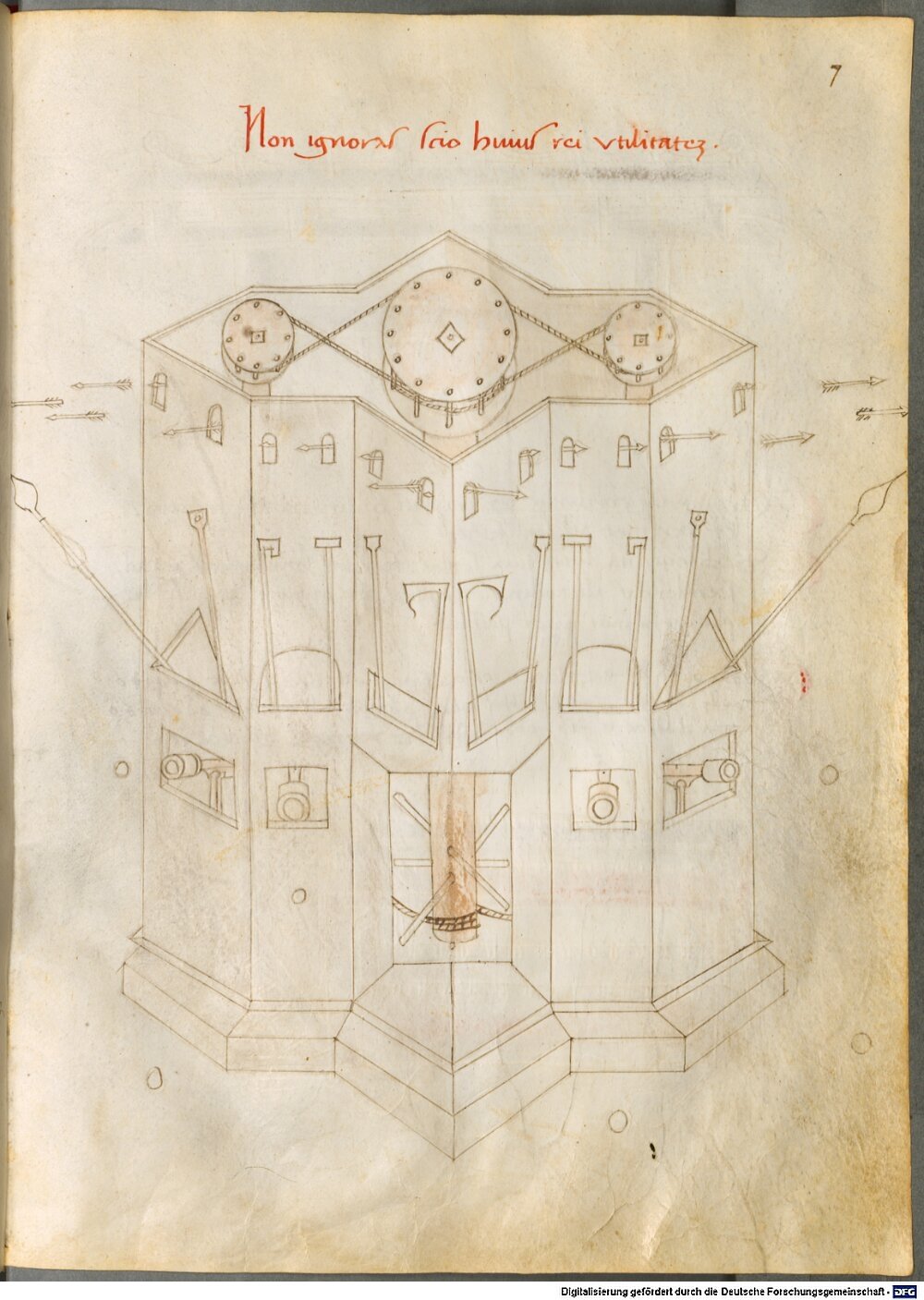

On yet another page, you see what appears to be a large fortified building featuring automated defences. Its articulated walls provide similar benefits to a star fort, resistant to gunpowder weapons and allowing firing angles on any hostile approach. From its lowest openings jut cannons, balls in mid flight on the page. Slightly higher, swing polearms with no visible wielders, and from the highest windows, arrows pour outward.

What makes this all particularly striking though is the thick wooden column appearing in the open doorway, rope wrapped around it and extending outward along with what seem to be wooden poles. The top of the building is open to reveal that this is one of three such columns, all linked by ropes through the metal wheels at their tops. The idea, it seems, is that the three pillars would be turned, by what power it’s unclear, and propel the walls’ layers of weaponry, so that some few defenders, or maybe even none at all, could bombard any would be attacker, on all sides of the building, with shot and polearm strikes. Not entirely practical maybe, but a compelling idea.

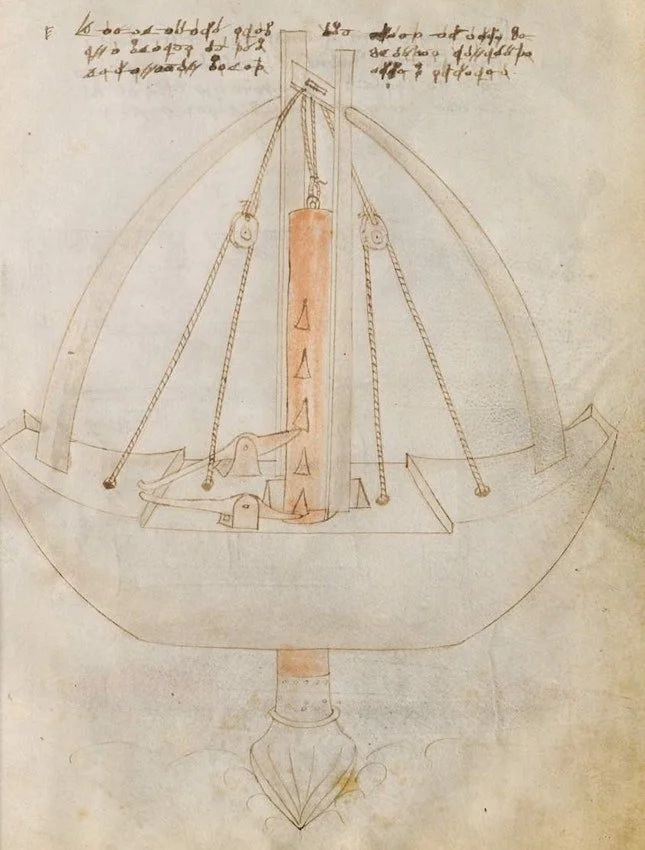

All of this is to say that there are indeed instruments of war there in the text. However, as I said, that’s not all that is there to be found. You can find something that appears to be an enormously thick harpoon shaft in the act of impaling a ship from above, which does sound like it would be used in war, but is actually an apparatus with which to retrieve sunken ships, something that has really never been easily done. You find what appears to be a large pipe organ, this one powered both by water and air. You find a skeletal figure rising and collapsing by cord and wheel, a way to bring the dead “back to life.” You find an array of instruments intended to be used during surgery, ones that enter the eyes and ears, the throat, something in the area of the stomach, a leg. Interestingly, there is also one that appears to enter the lungs and features bellows at the other to manually inflate the lungs if necessary. You find a range of clever locking mechanisms.

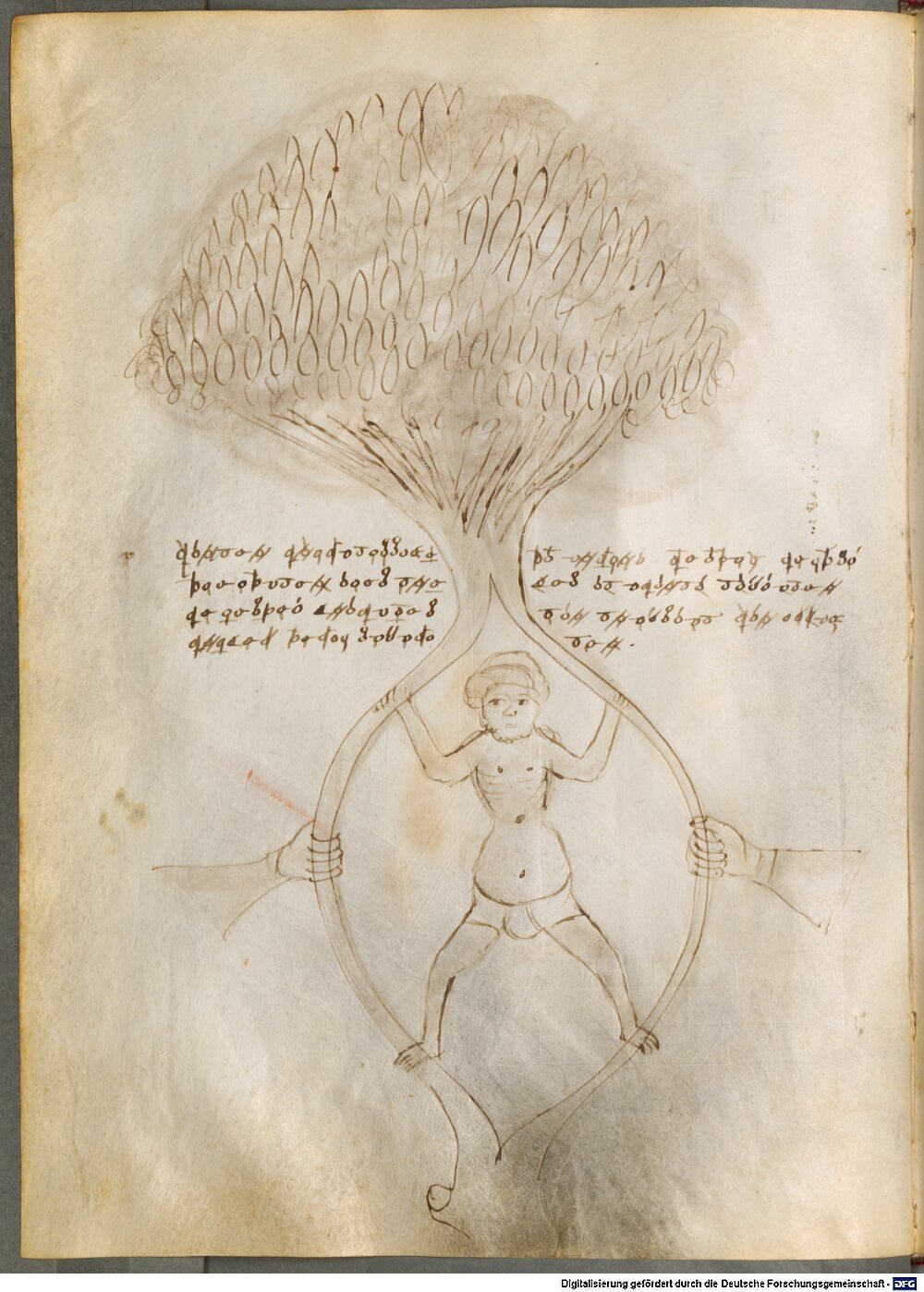

Some images in the text are not easily made sense of. One page features what appears to be a bush or tree with its trunk or root split and spread wide before rejoining at the bottom. Hands from either side pull the split section apart, and a human figure stands within it, limbs reaching out to the root/trunk on either side. It’s really hard to say what bit of Giovanni’s genius he was intending to communicate here, what principle might be on display.

On another page, the scene is absolutely industrial, though the purpose is unclear, with questions of scale in part responsible. How sizable is this machine, this peculiar contraption, with its screws, ropes, and pulleys, its chimney of fire, bending at jaunty angles at the top of the page? Other objects are more clear, even if scale remains an obstacle. That’s not actually a human gymnast, you realize, despite appearances. It’s a children’s toy, designed to hang, balancing, on a rope.

Giovanni seems to have put the full range of his knowledge and interest on the page, putting it all out there for potential patrons, if that was indeed his intent. And from his study of optics, he had not limited himself to just explaining away apparitions in the sky that had befuddled the peasants. He had applied his knowledge with some creativity.

There is the “magic lantern,” the earliest known depiction of its kind I have read, and a type of portable projector. It’s a bit different from the old ones in the classroom. This is a cylindrical device, shown held in someone’s hands, and on its surface the image that it would, when lit within, shine outward through its thin-stretched vellum. Not the notes for an upcoming test in this case, but a demon, complete with clawed feet, widespread wings, fangs, horns, and a fearsome-looking spear with extra pointy bits. Giovanni helpfully also drew the demon larger, above and to the right of the lantern and its holder, showing how it would look when projected.

There is also something a little more elaborate than this magic lantern, a kind of full-building artistic installation. It’s like a small, stylized castle, with its single tower rising up at the back and its battlements on two sides, almost a piece out of cut-out craft, the kind of thing you might pop out of a large-format children’s book and fold, with its lack of depth or, I guess you could say, thickness. In every room, what seem to be larger-scale magic lanterns shine scenes upon the walls. Passing through this multi-room spectacle, you could see knights jousting before rows of spectators and then, in the next room, watch deer dashing across the wall. You confronted scenes depicting birds, sword-fights, and what may or may not be angels. You can imagine how incredible a thing it would have been to experience, there in the first half of 15th century, were Giovanni actually able to pull it off.

Finally, in a non-exhaustive sense, there is that devilish automaton, sliding on a track across the page, its tail peeking out from under its clothes and trailing behind it, what appears to be fire blasting forth from its mouth and its ears. This figure, which I’ve also seen referred to as the “blazing witch,” could not only move back and forth across its rail but turn its articulated body, its head and wings linked to arms and tail. To its right on the page, one can see it with its outer shell stripped away, its inner workings there on display.

It was, as Grafton would remind us, the sort of thing that Giovanni rather favoured, performing works akin to magic but with his engineered contraptions, quote “visually mechaniz[ing] the apparently preternatural or supernatural. He made clear that his devices could create the same psychologically effective illusions as magical spells without invoking demonic power, and he denounced the fools who thought he conjured demons to achieve his effects.”

That aside, Giovanni was also putting on a show. Maybe he just knew what was liked and had a keen sense of selling the people what they wanted, but he seems to have had an affection for the spectacular, if one can read his character through those designs on the page.

As Bennet Gilbert writes in his Public Domain Review article, Giovanni’s designs were sometimes:

“…envisaged as elaborate displays for use in spectacles such as religious plays. Performed in front of churches and cathedrals, the shows would draw large crowds seated on bleachers, built to look like battlements, all around the stage. Medieval playgoers loved to see hell-mouths, angels flying down on wires, and heavenly clouds lifted and lowered by ropes.”

Giovanni, for all his many other interests and areas of fascination, seems, as much as anything to have delighted in the possibilities of putting on a show, of dazzling the senses. Maybe, I kind of think, he was driven by equal urges to education and magnificent illusion, but maybe that’s just me.

Whatever his true inclinations, we’ll set his story aside for now. I hope you enjoyed it.

I’ll be back next time with another medieval story. Thank you for listening. I’ll talk to you then.