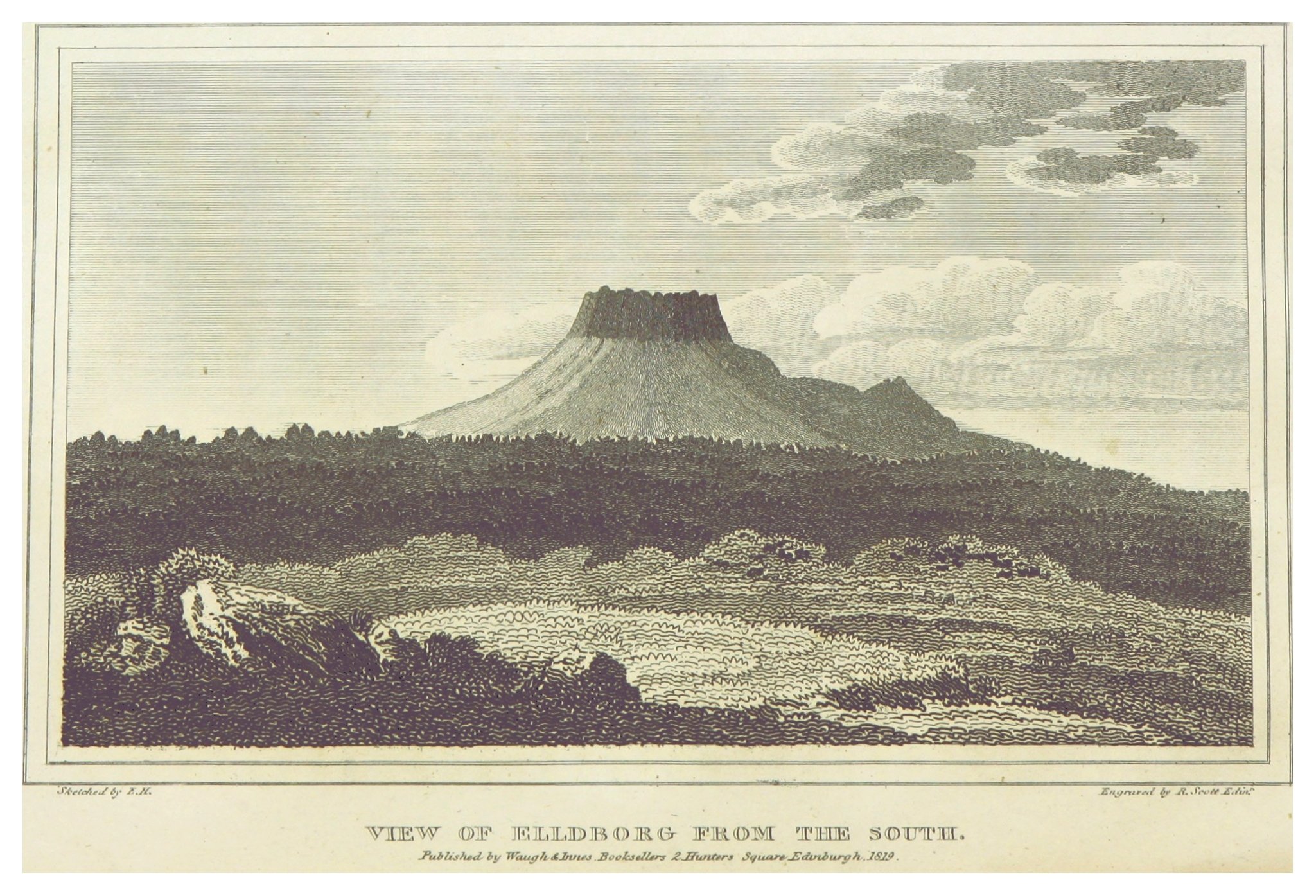

View of Elldborg from the South by Ebenezer Henderson - (British Library via Wikimedia)

YOU CAN LISTEN TO THIS EPISODE HERE OR ON YOUR USUAL PODCAST APP

When last we spoke, Grettir’s fortune, crucial in this context to a person’s lot in life, had turned for the worse. He had left advice unheeded and gone to fight the monster Glamr, and as Sophie Pavey has written, “Rather than returning to society as a hero who conquers the dark, Grettir [was] resigned to fear and inhabit it.” His luck, often spoken of in the saga, seemed to have run out, to have turned bad. Others observed it, and, as was the case with King Olaf of Norway, did not want such a cursed man anywhere near them. He went to Norway in search of glory at the side of that king. He returned with the inadvertent burning of a hall full of men hanging over him, with the outlaw status that resulted, with the sad news first of his father’s passing and then of his brother’s slaying at the hands of Thorbjorn Oxen-Might, a slaying which, in Grettir’s absence, had gone unpunished. At least so far.

That’s where we pick the saga back up.

We pick it up in the aftermath of Grettir’s return home, to the house that his mother still lived in. She had, remember, greeted him rather sadly on that occasion, not seeing a great deal of hope in his future or for that matter in that of her family as a whole.

Grettir stayed a while, not going out and making his presence known—for he didn’t want to bring further trouble there—but gathering information. You can imagine him there in the home, showing himself only to the friendliest of faces, and hearing from them what they heard and saw as they moved about the region, learning from them Thorbjorn Oxen-Might was to be found at home and unprotected, his men largely absent. It was not how you’d find me if I’d gone and murdered one of Grettir’s relatives, but then the news of his return to the district was still not widely known. Thorbjorn likely felt safe and secure in the inaccurate knowledge of his absence.

When Grettir came for Thorbjorn, as of course he did, as he always was going to do, it was in good weather that he rode to the home of his enemy at Thoroddsstead. He knocked on the door, greeted the woman who answered, and asked after Thorbjorn, wondering if he was at home, and if not, where one might find him. The woman, not recognizing this visitor, said freely that Thorbjorn and his sixteen-year-old son were out in the meadows binding hay. He thanked her, and off to the meadows he went.

When Grettir approached, Thorbjorn saw him coming, saw a stranger at first, then, as he got closer, a large man who could only be an avenging Grettir. He announced to his son that they must face their enemy bravely, that while he faced Grettir head on with sword and shield, his son should circle around to attack from behind with his hand axe, using two hands he specified, and striking between the shoulder blades. And so they tried to do, but in the end Grettir killed both of them, cracking the son’s head open with the blunt of his sword, and splitting that of the father with its sharp edge. As Thorbjorn had after having killed his brother, Grettir went and announced the killings, making no effort to conceal his responsibility.

A woman who had also been working that meadow ran to tell the people of Thorbjorn’s house that he and his son were dead, news that was greeted with shock. At Grettir’s family home, it was better received, his mother glad at what he’d done, what he had shown himself to be in properly taking revenge for his brother, but noting that he would hardly be able to stay there any longer. What was it he intended to do? To journey west, he said, and to seek out help from friends and kinsmen there. And so he did.

I should mention that he was in northwestern Iceland at this time, near Miðfjörður, and when he started out southwest for the home of his relative, Gamli, he was travelling roughly 30km by the modern roads, though he would not have walked them. There at Gamli’s home he was told that he would be given as much legal support as could be managed, but that he must leave the region. A long and largely lonely spell of wandering exile had begun.

He spent much of that autumn at Thorstein’s farm, but there was word that men were coming for him, and he had to move on.

It was Thorbjorn’s brother, a man named Thorodd Poem-Stump, who hunted him now, for he had taken responsibility for that duty in the aftermath of Thorbjorn’s death. He had been to see Grettir’s mother already and been sent off with her words that the killing had not been too much repayment for that of her son and besides Grettir wasn’t there with her. Thorodd had next discovered Grettir’s location at Thorstein’s farm, but Gamli had heard and sent warning, and Grettir moved on, advised by Thorstein on where to go next.

He tried a man named Snorri first, but though Snorri said he would be happy to speak for Grettir in any legal settlement, he himself was an old man and did not feel like harbouring outlaws if he was under no obligation to do so. Grettir went then to a farmer named Thorgils in the northwest as a second option and stayed there through the winter with a pair of other outlaws, their presence perhaps an indication of Thorgils’ remote location. The winter passed, not in peace, but without anyone dying, something that would not go unnoticed, credited to Thorgils’ character and luck, that he had hosted such uncontrollable men without violent incident. Of his guest Grettir, Thorgils remarked upon his great fear of the dark, Glamr’s curse still going strong, and how it would not allow him to go anywhere after nightfall if he could help it.

With the end of the winter season, came the althing, the gathering of powerful men from across the island with their followings, their causes and concerns, their agendas and grievances. Of course, the case of Grettir came up, the killing of his brother Atli, the killing of Thorbjorn Oxen-Might. There was actually discussion of acquitting Grettir, of relieving him of his outlaw status, for there were highly respected men who felt that he would be more dangerous, more source of trouble and harm, as an outlaw than not, and besides, his relatives were hardly likely to provide compensation for Thorbjorn’s death unless their payment was to bring Grettir some relief. But would Grettir be granted that relief? As you might have guessed, he would not.

The sticking point, really, was not the slaying of Thorbjorn Oxen-Might at all. That was a matter of negotiation, what with one farmer’s death potentially eye-for-an-eye equal to another’s. What proved not to be negotiable, and saw the althing conclude with Grettir very much still an outlaw, was that hall-burning from last episode. Thorir, father to those two sons dead in that hall, would not hear of forgiveness, legal or otherwise. His rage against their inadvertent killer was unabated, and he would not accept Grettir’s return to society.

He and Thorodd both placed prices on Grettir’s head, each an incredibly high price on its own, and though one of Iceland’s leading experts in law, a man named Skapti, again argued that “it was unwise to push so hard to keep the man an outlaw when he could cause so much damage. And he added that many would pay for this,” Thorir would not be moved. The one side offered the position that punishment in the strictest sense did not necessarily serve society best, but on the other was the anger of one who had lost two of his sons, and it was besides no average man who pursued this claim of retribution but rather one of significant power and influence. Grettir’s status stayed just as it was, and Skapti’s concerns were allowed to come true.

Grettir travelled north toward the western fjords, taking what he must, weapons from some small farmers, clothes from others, sometimes food, none of it given willingly, many of the owners treated roughly. A person like Grettir, cast out from society, had to take what they needed if they were able, and he indeed was able. Of that, there had long been little doubt.

At times, Grettir was careless, overly secure in his safety even as his condition became ever more fundamentally unsafe. He dozed off and was tied up by thirty herdsmen who fell to arguing over what to do with him, somewhat “three trolls squabbling over the fate of the dwarves,” before the intervention of a passing woman saved him from the rope. “What drove you to this, Grettir” she asked, when he’d identified himself. What brought you to his moment “that you trouble my [men],” for the land and men were those of her and her husband. “Some things just happen,” Grettir replied. “And I have to be somewhere.”

“Yours will be a great but difficult life,” said the woman’s husband when he met Grettir. “... But I have no wish to harbour you here and in return receive the anger of many powerful men. … few will be prepared to take you in if they can avoid it.”

Such speeches addressed to Grettir often put me in mind of Watership Down, of that of Lord Frith to the father of all rabbits: “All the world will be your enemy, Prince with a Thousand Enemies, and whenever they catch you, they will kill you. But first they must catch you.”

Being tied up by herdsmen aside, catching Grettir was not so much the problem, for he was not really the “digger, listener, and runner” type of Watership Down. Never particularly rabbit-like, his survival skills lay elsewhere.

Winter passed in the home of a kinsman, a skilled smith who soon tired of Grettir’s disinclination to do any work and besides heard that his guest’s enemies had learned of his whereabouts and were again gathering. Spring and summer passed on a mountain from which Grettir robbed passing travellers, each one contributing from their belongings with no choice to refuse, each one everyone except for one man who alone had the strength to keep what was his, to yank his own reigns back out of Grettir’s grasp and ride confidently on, telling Grettir in riddle and verse where he lived and filling him with with wonder at the power he’d in this stranger’s grip.

It was understandable that a man in Grettir’s position might be forced to resort to such brigandry, that he had not a great deal of choice in just how he lived, but not everyone saw it that way. Skapti, that sympathetic expert in law, told him his behaviour was unworthy of a man of his lineage and, more immediately, unhelpful for a person of his legal standing. Moreover, Skapti himself could hardly entertain such a man as a guest. He advised him to find someplace where he could live on his own resources, to find his way independent of theft and violence, but Grettir, though he saw the wisdom in this, complained that he could hardly manage to live alone with his terror of darkness. He could scarcely tolerate it, but he would need to try, for as Skapti replied, he could hardly hope now to have it all as he wanted.

Grettir did make an effort to change his way of living. He took himself even more aside from society, finding a good situation next to a lake. He arranged nets and a boat to fish for his food so that he wouldn’t need to waylay travellers, and he suffered. He was miserable in his wilderness retreat, possessed of a loneliness driven by fear, and this fear of being alone, it made him vulnerable.

After this short break, we’ll see just how vulnerable.

…

Though Grettir had sought and found a place where he could make his way away from others, others found him. Other outlaws heard of Grettir’s hideout there and they came, most hoping for his protection but some came for other reasons. A man named Grim came, claiming a desire for company and protection, but secretly planning to kill Grettir for money along with the promise of freedom and forgiveness from his own outlaw status. Late into that autumn he stayed with him, and when he thought he had his opportunity, Grettir was ready for it and killed him. Grettir, the saga once more emphasizes, was distressed by nothing more than the dark, and winter passed with him alone and afraid.

Ever distrusting, always needing, he learned from Grim’s assassination attempt, but that didn’t really change anything in the choices he made. He knew the food was bad for him, but still he ate, feeling he had no other choice. Being alone was simply that much worse than worrying about whether a stranger would attempt to kill him, truly an unpleasant way to live.

So it was that when another outlaw came along after the winter, this one named Thorir Red-Beard, Grettir allowed him to stay. He didn’t trust him, and indeed he was correct in his distrust, for Red-Beard had been sent by Thorir of Gard, father of the two brothers who had died in the hall-burning. Red-Beard was himself a noted killer of strength to rival Grettir’s, and he had also been promised rich rewards and an end to his punishment in exchange for Grettir’s head. Grettir suspected him, but again, so desperate was his condition that he had to give him the benefit of the doubt, to trust him, for now, and allow Thorir to stay, even if he could not fully let his guard down around him.

Through a full two winters Red-Beard lived with Grettir and waited for a chance to kill him. It was a serious commitment to an unpleasant and difficult task, and the way the saga reads, it seems he eventually just despaired of receiving a better opportunity and tried to manufacture one, to force the issue. It was a stormy night in the spring, when Grettir woke up and asked whether their boat was secure, and Red-Beard leapt up to go check. He went outside and smashed the boat, scattering the pieces about as if this violence had been done by the wind and sending the nets out into the water before going inside to inform Grettir that the storm had badly mistreated them. Grumbling, Grettir came outside to see for himself.

There was talk over who should swim out for the nets, with Grettir insisting that Red-Beard should do it while Red-Beard protested that swimming was the one physical exertion that he could not manage. Eventually, Grettir set aside his clothes and weapons and prepared to dive into the dark and surely very cold waters, telling Red-Beard all the while not to betray his trust in him.

“Stop accusing me of treachery and cowardice,” said Red-Beard, for it had been more than two winters.

“You alone will prove who you are,” replied Grettir, and so it soon proved to be true.

When Grettir had gathered the nets and was climbing back up the banks of the water, Red-Beard rushed upon him with a raised sword, but just as he swung, Grettir hurled himself backward into the water and dove under. Red-Beard waited, watching the surface and preparing to strike, but Grettir stayed under and swum along the bank and around the point, coming ashore behind Red-Beard and approaching him quietly so that there was no warning until Red-Beard was suddenly hoisted bodily into the air and then sent crashing to the ground, his head then quickly cut off with his own sword. “After this,” the saga’s passage concluded, “Grettir never had anything more to do with outlaws. Still, he could not tolerate being alone.”

When Thorir of Gard heard word that Red-Beard had failed, time had not appeased his anger, not two years of. The setback only encouraged him to take a new tack. Hiring a single assassin seemed not to be the answer, so maybe just going up there himself with a small army would work. He would certainly try.

Thorir went with 80 men, and Grettir was warned of his approach, harder to conceal than the movement of a solitary outlaw, but Grettir did not flee before his coming. He looked out for it, and when he saw a large group of men riding his away, though not yet realizing quite how many they were to be, he left his hut and climbed up to a narrow place at the peak where very few could assault him at once. Thorir, seeing him trapped there, gloated at a job all but done and commanded his followers to go and take his head, but Grettir, in one of the better understated lines of the saga, replied that “Arriving at the well is one thing; drinking is another. You have long sought this moment, and some of you will acquire marks of the game before we part.”

The attack began, and from his place in the narrows, Grettir took on all who rushed at him, striking some back, others down, none of those who were able to fit through the opening able to do much to trouble him, but as the fighting went on, what Grettir found strange was that none even attempted to trouble him from behind, to sneak around and attack his unprotected back. Thorir, knowing full well that he had sent men round the back, was also struck by this, though he reacted differently.

“I had heard it said that Grettir was a champion because of his strength and courage,” he said. “Still, I had not understood that he was as filled with sorcery as now I see, because behind him twice as many men are killed as from the group that he faces. Now I realize we are dealing with a troll and not with a man.”

For Thorir, that was enough. He called his people to withdraw, and he departed in what would be counted by many a shameful defeat that ended with 18 of his own men dead and many more than that wounded.

Meanwhile, Grettir had turned to investigate exactly what had gone on behind him, and climbing that way he had discovered an enormous man seated against the cliff wall and covered in wounds from Thorir’s men who he had fought off. Who was he, Grettir asked.

“He” was Hallmund, “and I can give you this clue to aid in remembering me,” he told Grettir. “You found I held the reigns tightly when we met … during the summer.”

It was the man Grettir had met a few years before, the only one who’d been strong enough to be able to say no to him, back in his time of brigandry, the one who had given him quite a different name on that occasion, and who now, inexplicably, was here, at Grettir’s back warding off his assailants and inviting him to come stay in his home, a quote, “large cave [with] a large, impressive daughter,” for, as Hallmund put it, “you must find it lonely here.” Grettir happily agreed, ever longing not to be alone, especially at night, and now at least finding someone he could surely trust.

In the home of his mysterious benefactor, Grettir stayed a long time that summer, healing and resting, composing verses dedicated to his new friend:

“Swords with an adder’s bite

glided on wounding paths

through flesh and bone, as fighting

raged at Hrutafjord.

Now those thugs are hosting wakes

for the dead killed at Kelduhverfi.

Hallmund climbed from his cave

to aid me in my escape.”

As I’m sure many others have before me, I do wonder about Hallmund. Going under different names, living, as he’d told Grettir when they’d previously met, “beyond the dwellings of human folk,” in a cave as it happened, out there in the wild, and with an unusually large daughter. Was he, were they, actually human, or entirely so? In this saga, it’s not totally clear.

Whatever else he was, Hallmund was a good friend to Grettir. There seems, and perhaps I’m reading too much into the material, but there seems to have been a note of real warmth and affection here that you would not necessarily expect from someone you first met in an attempted robbery on a mountain path, and that’s admittedly a low bar, but there is something special to the friendship.

Grettir seems to have been happy there with the two of them, but he did not stay. He expressed a wish to “return to the inhabited districts” and to see his kinfolk once more, for it had been a while, and in the autumn of that year, he left that friendly cave.

Three winters he spent abroad in the west of Iceland, burning bridges and generally outstaying his welcome. There was a long period in which he camped out in a lava cave overlooking a path commonly used by travellers and again took to robbing them until various groups mustered against him. In one encounter, he maimed and injured several men, slicing one through the waist, nearly in half. Killing another, named Steinolf. To the woman of nearby farm who saw him pass by after the fight and asked for news, he answered in verse, rather dryly:

“I tell you, attentive lady,

those grievous wounds to the head

that Steinolf took won’t heal

in a hurry.”

Steinolf’s head had apparently been split straight down to the shoulders.

In another incident, an overconfident opponent came against him with all their followers, but when those followers had begun to fall and he had personally exchanged a few blows with Grettir, he turned and ran, Grettir offering pursuit but not really chasing him over a mountain, through a valley, and on past other landmarks. Just going fast enough to keep close, to press the fleeing man. Giving him just enough room to throw aside some item or other that might be slowing him down. His weapons first, then his clothes and other belongings. When he was down to the underclothes, Grettir finally closed in. He beat the man with a birch branch before releasing him and going back to his lava cave, picking up what the man had dropped along the way.

Grettir could not stay in that cave forever. He’d killed or robbed too many local men, an increasing number of them friends and kinfolk to the man who’d suggested the place to him in the first place, his host there. He had to leave, and after about three years he did so.

There was time spent in the valley of a half-troll and shepherd named Thorir, time, apparently very enjoyable time, spent with the half-troll’s daughters. There were travels in the East Fjords, but none of the leading men there would have anything to do with him. None would give him shelter or food. None would offer him the kindness that Hallmund had.

As for Hallmund, while Grettir had travelled, and robbed, and generally misadventured about, Hallmund had noticed that another outlaw had taken up residence in the home where Grettir had once stayed and fished. Grim, for that was the outlaw’s name, had killed someone and been cast out because of it, and he now found Grettir’s old shelter as good a place as any to stay, situated as it was next to a lake abundant with fish. But Hallmund didn’t like this, didn’t like that this newcomer was taking advantage of what had once belonged to his friend. He decided that no one else ought to benefit from that place.

From Grim’s perspective, the fish began disappearing one day, not from the lake but from the racks where he hung them after he’d brought them ashore. Fully one hundred fish simply gone the following morning, and the next time he fished, two hundred. The third time, he resolved, would be different.

He caught three hundred fish that day, and he prepared and hung them outside his new home as he usually would. But this time, he waited in secret to see who or what would come. He waited into the night, until he heard heavy steps approaching. He watched as a large man carrying a large basket appeared and walking up to the racks stuffed all the fish into the basket, enough that it would have taken a horse to carry more. Then, as this stranger rose with his burden, Grim rushed out, axe in hand, and buried it, two-handed, in Hallmund’s neck.

Hallmund staggered to his feet, basket still slung across his back, and set off at a run, Grim, filled with curiosity, following him all the way to his cave and his daughter, described again here as “large but good-looking.”

Then, as Grim watched unnoticed, Hallmund greeted his daughter and, when questioned about the blood, answered in verse:

“No man can trust

in his own unaided

strength, that’s clear

to me—because

the courage of heroes

ebbs away

on the death day

as their luck runs out.“

And he told her just how his luck had run out.

“This was not the kind of man to let things pass,” she said, “nor is it surprising, considering how you treated him. But who will now avenge you?”

“It is not certain that vengeance will be taken,” answered Hallmund. “I believe Grettir would seek to avenge me, if he were able to come. Still, it will not be easy to go against this man’s good luck, because his future is bright.”

At the end, Hallmund told of his many exploits in verse, going on for some time because his life had been full of travel and adventure.

“Trolls and their kindred,

who dwell in the crags,

I have dealt with harshly.

I have taken on many

evil creatures.

Half-breeds and half-trolls

met death through me.

Likewise, I’ve shown

hatred to almost all children of elves

and evil spirits.”

There was much more, some of it concerning his time with Grettir that showed pride, affection, competition:

“My strength was esteemed

when with force enough

I buffeted Grettir

away from my reins.

With a glance I saw

how he stood gazing

a good long while

down at his palms.

Next was the time

that Thorir ventured

onto the heath

by Arnarvatn,

and just the two

of us enjoyed

a game of spear-points

against their eighty.

Grettir’s hands

showed the form of a master,

with glancing blows

against their shields;

I heard, though, that our

opponents rated

the marks left by me

more severe by far.

As for those fellows

who sneaked from behind,

I sent their hands and

their heads flying,

with the end result

that eighteen bodies

from Kelduhverfi

littered the heath.”

And when he had finished his poem, he died, and his daughter broke down into tears. Grim stepped forward then, presenting himself to her and urging her to take heart, though not as one would now. “Everyone must die when his time is up,” he said, “and this end was largely caused by his own actions. I could scarcely sit by and watch him rob me.” And to this, she agreed.

Grim stayed there in the cave many nights, and by the time he left, he had learned Hallmund’s poem. The narrator tells us that he “later became a trader, and many stories are told about him.”

And that was nice for Grim, but for Grettir, he had lost another who was close to him, and there were not all that many of those. As Hallmund had told his daughter, Grim’s future was bright, but the same could not be said for himself or for Grettir. Perhaps his misfortune was in part borrowed from that of Grettir, that cursed aspect to our protagonist which many had recognized and steered well clear of. Next time, we’ll follow that unfortunate aspect toward its conclusion.

Thank you for listening, and for your support.

Sources:

Grettir's Saga, translated by Jesse Byock. Oxford University Press, 2009.

Grettir's Saga, translated by Denton Fox and Hermann Palsson. University of Toronto Press, 1974.

Pavey, Sophie. "Outlawed but Not Alone: Friendships Out of Bounds in Grettir’s Saga," UBC Arts One, Prof. Miranda Burgess Seminar, 2021.