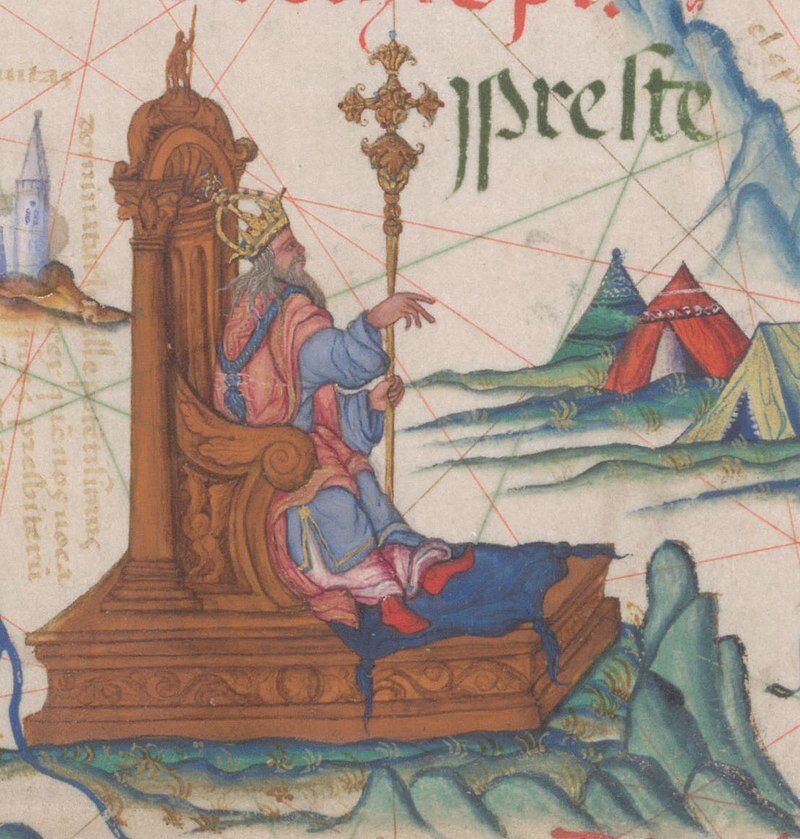

Prester John in the Queen Mary Atlas (Wikimedia).

YOU CAN LISTEN TO THIS EPISODE HERE OR ON YOUR FAVOURITE PODCATCHER.

We’ll start this episode with a passage from the writer of the 19th century hymn “Onward, Christian Soldiers,” and no, that is not a joke.

It just so happens that the hymnist in question, Sabine Baring-Gould, had other arrows in his quiver than just that. He was, in addition, a novelist and a collector of folk songs, who also wrote about today’s topic in his book Curious Myths of the Middle Ages.

What he wrote on the matter could be said to speak to us as much of the 19th century as it does of the 12th, as much of the modern world, with all of its prejudices, as the medieval one. That tends to be how it works. What he wrote begins like this.

Quote:

“About the middle of the twelfth century, a rumor circulated through Europe that there reigned in Asia a powerful Christian Emperor, Presbyter Johannes. In a bloody fight he had broken the power of the Mussulmans, and was ready to come to the assistance of the Crusaders. Great was the exultation in Europe, for of late the news from the East had been gloomy and depressing, the power of the infidel had increased, overwhelming masses of men had been brought into the field against the chivalry of Christendom, and it was felt that the cross must yield … .

The news of the success of the Priest-King opened a door of hope to the desponding Christian world. Pope Alexander III. determined at once to effect a union with this mysterious personage, and on the 27th of September, 1177, wrote him a letter, which he entrusted to his physician, Philip, to deliver in person.

Philip started on his embassy, but never returned.”

Leaving aside for now questions about his embassy, Philip would not be alone in his failure to locate and reach the priest-king. In between references to “the odious crescent” and the Mongols as “Gog and Magog come to slaughter, and the times of the Antichrist,” Baring-Gould traced a dramatic story of friars sent forth into the steppe, of the resultant reports that no, there was no mighty Christian empire out there, of how some set their eyes on Africa as a possible home for the legendary ruler, of how others still maintained that, quote, “the Prester John of popular belief reigned in splendour somewhere in the dim Orient.”

In this series, we’ll be exploring some of those not-so-dim regions and this cultural giant who was projected to pop up here and there across them at different times and in slightly different guises, not exactly real, save for the real impact that he had upon the world. We’ll follow this recurring character as he skips across centuries of chronicles and travel narratives, sometimes one man, sometimes a dynasty, a figure, or figures, of mystery, always at the edge of one’s vision or else found but not quite living up to the reports. This will be his story, and that of those who told stories of him.

Hello and welcome. My name is Devon, and this is Human Circus: Journeys in the Medieval World, the podcast that follows medieval history through the stories of its travellers, through its merchants, monks, and ambassadors, both real and imagined. And it is Patreon supported, supported by podcast listeners like yourself, maybe even actually yourself, you who are listening right now, in which case thank you very much! Patreon membership starts at a dollar a month, but if that’s not an option for you, and I fully appreciate that sometimes it simply isn’t - it’s a costly world and one has to be able to eat and so on - so if that isn’t an option for you but you are enjoying the podcast, then please do consider leaving a review wherever it is you listen. Positive reviews help the podcast reach new listeners and also help counteract the ones from people who, for example, don’t like my voice, or are otherwise against the whole thing.

That said, let’s get into the story.

It’s the mid-12th century. The Knights Templar have been founded not so long ago. There is a Norman king in Sicily, and a Plantagenet in England. Frederick Barbarossa is Holy Roman Emperor. Abelard has died, then his antagonist Bernard of Clairvaux, and then Héloïse. Construction begins on the Notre-Dame. The Second Crusade comes and goes.

The crusade is not a raging success, not for Conrad III or Louis II, both of whom suffer significant defeats in Anatolia at the hands of the Seljuks and then later fall short at the Siege of Damascus. Better for someone like Nur ad-Din, who we met in the Salah ad-Din series, and who here featured on the other side of those encounters.

It’s around this time that a document is written and it circulates, a document with a story to tell, a story that would be every bit as impactful as it was untrue. Indeed, the life this story will have seems to make its truth value, any question of whether what it says is or is not so, seem almost trivial by comparison.

Some time ago on the podcast, I covered John Mandeville, the widely travelled and widely read English knight whose text and general character turned out to be widely borrowed from other sources. And that was quite some time ago, pre-pandemic if I remember correctly. I finished that last Mandeville episode by saying that I was leaving out the material on Prester John specifically because I would be back soon with a full series on Prester John, and that I would be back with the start of that series in the next month or so. Things don’t always go as planned.

As you now know, I was not back with the start of that series in the next month or so, not in the month or so after that either. Not even in the month or so after that. But I am now.

This is the story of a mysterious priest king, a Christian ruler of unimaginable power, a man of great wealth both in worldly riches and wondrous miracles. A mighty lord whose armies marched forth from somewhere in India, or the steppe, or perhaps East Africa. A would be saviour to which Latin Christian Europeans looked in hope. A figure in fiction all the way from Umberto Eco’s Baudolino to the Marvel Comics universe where he wielded an artifact from the land of Avalon known as the Evil Eye and was preserved for centuries in the Chair of Survival, which I think is totally appropriate given how long he lingered in the imagination as an impactful person.

This is the story of Prester John.

Where to start?

Maybe we should start with a text from the first half of the 12th century, uncovered in the last half of the 19th, a text telling of the coming to Rome of a patriarch from India, of his arrival during the 4th year of the papacy of Calixtus II, during 1122.

This patriarch had apparently been elected by the Christians of India and had immediately journeyed to Constantinople for confirmation of his rank. He had there encountered papal legates and with the help of Greek interpreters arranged to be brought on to Rome, to see it with his own eyes and be able to report back. His presence in that city was written of as in itself being a miracle, for nobody, quote, “from such distant lands and barbarous regions [had] ever been seen throughout almost all of Italy besides this aforesaid Patriarch John of blessed life.” His name, by the way, was indeed John.

This John was said to have leapt for joy and praised God on sighting Rome, and after he spent some time in the city and learnt something of it, he spoke one day, before the pope and a large congregation, of the lands he had come from.

He spoke of the city of Hulna, “head and mistress of the Indian kingdom.” It was a full four days’ journey across, surrounded by walls wide enough for two chariots to ride atop them side by side, and enriched by the jewels from one of the rivers of paradise, that flowed through it. The entire city was populated by Christians, and as related in the Acts of Thomas, no one of other beliefs could live there without soon converting or else collapsing dead.

Nearby, there was a lake, and on its shores were twelve monasteries, each dedicated to one of the twelve apostles. In the centre of that lake was a mountain, and at its summit, the church of Thomas himself. That church was inaccessible save at the time of the yearly feast when the waters receded and people gathered to celebrate and be healed, and the patriarch entered the church to practise the sacred mysteries.

Inside, set within an ornate canopy crafted of precious metals and stones, was a greater treasure still, the body of Thomas, upright, “whole and unharmed as though on the day of its burial.” Before it, hung a balsam-fuelled lamp, never diminished, never extinguished, and during that festival of the holy apostle, people would shout and clamour for some of that balsam, known and desired for its miraculous healing properties.

The body of Thomas was taken from its perch and placed upon a throne. He made a handsome figure, red in hair and beard, face glowing like a star, and when the patriarch approached him with “holy offerings in [a] golden pan,” Thomas took them in his outstretched right hand, “so that he [was] believed to be not dead but altogether alive,” and the saintly body administered the Eucharist. But when the faithless or corrupt approached, Thomas would withdraw and close his hand, refusing to give his blessing. Thus rejected, the disbeliever would immediately be brought to convert or else would die upon leaving that place, and at this fearful miracle, all those watching who were not Christian would be moved to convert in a great wave.

At the end of the week of celebration, the patriarch and his ministers returned Thomas to his place of rest, and the people left his church, the lake, which had dried up to permit their passage, filling again behind them with deep water.

Quote:

“When the patriarch of the Indians had finished reporting such things in the Lateran court, Pope Calixtus the Second, who was there with the rest of the Roman assembly, calmly glorified Christ, with their hands raised to heaven, because so excellent and so great a miracle did not cease to be performed through his holiness the apostle Thomas every year, with the father and the holy spirit living forever and ever.”

Maybe instead, we should start with German chronicler Otto of Freising and his Chronicle or History of the Two Cities, recorded between 1143 and 46. That’s often referenced as the first appearance of Prester John, so what did that entail?

According to Otto, he had heard the story when at the court of Pope Eugenius III and had heard it from Bishop Hugh of Jabala. The bishop had been there to urge the pope that Edessa had to be retaken, but Hugh had also told of a man named Johannes, or John, a man both king and priest whose lands could be found further east than Persia and Armenia, who, like the rest of his people, was a Nestorian Christian.

This John had not remained out there beyond Persia and Armenia but had in recent years come against what is described as a combined army of Persians, Medes, and Assyrians and, after three days of slaughter, a deadlock in which neither side would submit, had won victory and swept forward, toward Jerusalem. He would not reach it.

Quote:

The Bishop said that the aforesaid John moved his army to aid the church of Jerusalem, but that when he came to the Tigris and was unable to take his army across it by any means, be turned aside to the north, where he had been informed that the stream was frozen solid during the winter. There he awaited the ice for several years, but saw none because of the temperate weather. His army lost many men on account of the weather to which they were unaccustomed and he was compelled to return home. He is said to be a descendant of the Magi of old, who are mentioned in the Gospel. He governs the same people as they did and is said to enjoy such glory and such plenty that he uses no sceptre save one of emerald. Fired by the example of his forefathers, who came to adore Christ in the manger, he proposed to go to Jerusalem, but he was, they say, turned back for the aforementioned reason."

John, the promised priest-king of somewhere out east had brought his army to the verge of intervention in the crusader states, had been on the cusp of bringing that army to Jerusalem itself, and then faded away. And who was he?

Historians usually identify the story of this John with that of Yelü Dashi, the man who escaped the collapsing Liao dynasty and led his people west, establishing the Qara Khitai and, crucially to our concerns, achieving a stunning military victory against Seljuk Sultan Ahmad Suljar at the 1141 Battle of Qatwan. The timing was right, but In some ways there seems little of the Prester John legend in this leader from northern China who founded an imposing Central Asian power. He was, I should clarify, not Christian. I have variously seen him described as Buddhist or Buddhist-Tengrist, though that was not at all understood by Otto, his source, or his readers. Yelü Dashi was, critically, not a Muslim, and thus, it seemed, believably a Nestorian Christian. He had arrived from distant, only vaguely understood lands to the east and defeated a strong Muslim leader of considerably greater proximity. You could see how that might be interesting, how stories might grow, how they might have joined those that had already grown.

For what it’s worth, neither Otto nor the pope seems to have fervently invested their hopes in this particular supposedly Nestorian saviour. Otto passes over the material in a manner that historian Keagan Brewer describes as being, quote, “almost as though it were unworthy of being recorded,” though the levels of belief or disbelief are difficult to assess. And as for Eugenius III, he would act on the primary topic of Bishop Hugh’s embassy, the urgent need to retake Edessa, but he appears not to have attempted contact with the priest-king Johannes.

Maybe, instead of either Otto of Friesing, the chronicler of reports of a far-off battle and failed attempt to intervene in Jerusalem, or Patriarch John, witness to a land of Christian miracles in India, we should start with the letter. Maybe we should start with the epistle of Prester John that circulated in the late 12th century. It was, according to Aubry de Trois-Fontaines, sent in 1165. Aubry was writing after 1232, so it’s not clear that he would know exactly, but that or thereabouts, remains the widely repeated date.

We’ll start with that letter after this quick break.

...

The “letter,” in translation, begins like this.

Quote:

“Prester John, by the power and virtue of God and our lord Jesus Christ, lord of lords, to Emmanuel, governor of the Romans, wishing him health and the extended enjoyment of divine favour.”

Emmanuel, the Roman governor in question, was Manuel I Comnenus, ruler of the Byzantine Empire from 1143 until 1180. As for Prester John, maybe we should start with the basics.

First of all, Prester, or Presbyter, John, to be totally clear, wasn’t real. He did not really exist, except in the sense that he did, that he did have a real impact in shaping the world as some people saw it. He was, or so the stories went, a Christian patriarch whose armies promised to spill forth from behind the borders of his near-magical realm and to occupy the Holy Land, an external saviour whose arrival some European Christians would look to with hope, a redemptive and irresistible force sweeping in from the east. Or if not him, then perhaps his son, or his grandson. Over time, the promise of the bloodline would replace that of the man himself. It could not help but do so as first decades and then centuries passed. His realm was said to be miraculous, but he was not expected to have so much of a miraculous lifespan as that himself.

The Prester John of the letter addressed himself to a Byzantine emperor who the, quote, “little Greeks” regarded as god, though he was known by the writer to be only “mortal and subject to human infirmities.” There are also other little jabs at the Byzantine emperor and the nature of his Christianity. This Prester John promised that should Manuel wish to visit him in his realm he would be set by his host in a place of the highest possible dignity and when he returned to his own lands would do so with great riches. Then he started to tell him of the greatness of that realm, in riches and otherwise. As to that, the letter writer was not shy. Indeed, he embarked on what has been called "an orgy of unrestrained grandiloquence."

“If you truly wish to know the magnitude and excellence of our Highness and over what lands our power dominates, then know and believe without hesitation that I, Prester John, am lord of lords and surpass, in all riches which are under the heaven, in virtue and in power, all the kings of the wide world. Seventy-two kings are tributaries to us.”

He would have more to say shortly on the topic of his immense wonderfulness and that of his lands.

After establishing the excellence of his power and the number of the kings beneath him, only few of their provinces Christian, the writer got to the really promising bit, at least where some in his audience were concerned. He said that he was a devout Christian and one who everywhere defended Christians. He said that he had vowed to visit the Sepulcher of the Lord with, quote, “the greatest army, just as it is befitting the glory of our majesty; in order to humble and defeat the enemies of the cross of Christ and to exalt his blessed name.”

So there was that. And just in case his reader should doubt that Prester John was capable of such things, the writer got a little more expansive.

He wrote of magnificence that dominated lands from the furthest reaches of India, where the body of the apostle Thomas rested, to the slopes of the Babylonian desert. Of the creatures and peoples that lived there, of elephants, dromedaries, camels, hippopotami, crocodiles, white and red lions, wild donkeys, silent cicadas, methagallinarii, cametheternis, and thinsiretae, those last three seeming to be hybrid creatures of different kinds. Then there were the white bears, white merlins, centaurs, cyclopses, griffins, wild men, horned men, fauns, satyrs, pygmies, dog-headed men, giants, and phoenixes. There were salamanders, creatures which lived in fire and produced silk. There were fish whose blood produced a purple dye.

There was a place abundant with honey and abounding with milk. A place without scorpion, snake, or noisy and, it would seem from the context, venomous frog. There is a river flowing from paradise that winds its way through, and in which are found natural gems of all kinds. There is a plant which grows there whose root drives off unclean spirits. There is a woody land where pepper is grown but is overrun with serpents. When it is time to harvest it, the woods are burned, driving the snakes into their holes while the pepper is gathered.

There is a spring that varies in taste by hour of the day, and if you drink it after fasting for three days, then you will never age, no matter how long you live. There are small gems sought by eagles to restore their sight that if worn by a human on their ring, sharpen their vision. Properly prepared, it could also make them invisible, charm those around them, and banish envy.

Near the home of the ten tribes of Jews, there is a river of stones that runs for three days a week and flows into a waterless sea, the sea’s shifting sands uncrossable by any ship and whatever lands lie beyond it completely mysterious. There is a place where the land may open up beneath your feet, and if you are quick, you can snatch up a handful of precious gems before it closes. There are deeper caverns, beneath the ground and beneath the water, where more gems can be found, and in that area, children are raised in the water so they will later be able to spend months beneath the surface collecting them.

The writer wanted you to know that there were riches, that neither visitor nor inhabitant need want for anything. With all that wealth, there was no room for theft or greed. Such behaviour had no place among all that abundance, not theft and not falsehood. There were no liars among these people. Those who did tell a lie, died immediately—figuratively speaking, the writer was quick to clarify, for such a person was dead to their society and would never again be spoken of by them. This is a place without vice, without adultery, without flaw. Its ruler sleeps on a bed of emerald, “on account of the stone’s virtue in chastity,” though not the kind of chastity that prevented beautiful women from arriving 4 times a year, purely “for the purpose of procreating children” before returning to their homes.

Within this medieval utopia, the priest-king himself ruled from a rich palace, built in the likeness of that which Thomas the apostle had once designed for a certain Indian king. It is all in acacia wood and ebony, lit by balsam torches, and sparkling by day with the light reflected off two large golden apples and by night from two large, red gemstones. Those within dine off tables of gold, emerald, or amethyst, kept safe from poison by the serpent’s horn inlaid into the gates, and, one might assume, by the spotlessly crime-free nature of the wider society. The author doesn’t exactly paint a picture of a realm in which there are a lot of deceitful, murderous poisoners running about. But there is conflict. It’s not clear exactly who with, but there is talk of a place near the palace where the fighters struggled. It almost sounds like they did so in a kind of eternal combat there before the gates, striving without respite or end.

Near that place, and near the palace, is a peculiar feature, only reached by 125 steps, first of porphyry, serpentine, and alabaster, then crystal, stone, and sardonyx, and for the final third, amber, jasper, and sapphire. Climbing alongside, or perhaps within, these stairs, are a series of columns, at the base one, and on it two, and on them four, and so on, in a vast inverted pyramid of columns that widens out to sixty-four columns before narrowing back down. At the peak of this precarious architectural diamond is a mirror, not a regular mirror of course.

I’m reminded here of the story of the mirror that was supposed to sit atop the lighthouse of Alexandria, the one that could be turned against enemy fleets, burning them at sea before they could threaten the harbour, the one that was supposedly sabotaged, smashed by a treacherous priest if I remember the story correctly. This one didn’t exactly have that power. What it did have was something else rather special. In this mirror, Prester John and his people could see all plots and machinations, in fact all things that were put in motion for or against him in the other regions of the land. Guarding this powerful mirror against the fate of its Alexandrian cousin, this one was protected day and night by twelve thousand men.

And there was more. This “Prester John” was not yet done, was not yet certain you were appropriately impressed by his tremendous tremendousness, was going to show you by way of those who served him. His “steward is a primate and king, [his] cup-bearer an archbishop and king, [his] marshal a king and archimandrite, and [his] chief cook a king and abbot.” There is talk of how kings took turns serving him, seven in a month, along with sixty-two dukes, and a pleasing 365 counts, how twelve archbishops ate at his right and twenty bishops at his left, along with the Patriarch of St. Thomas, the Archpriest of Samarkand, and the Archbishop of Susa, connecting this Christian kingdom to concrete real-world locations. All told, 30,000 ate every day at his court.

And if the priest-king writer still hadn’t convinced you, then he was happy to tell you of a second palace. This one was not wider but was taller and more beautiful than the first, having appeared to Prester John’s father in a vision, in a dream. He had heard the words that he should construct a palace for his son, his son who, he was told, would be “king of the worldly kings and lord of the lords of the entire Earth.” He was told that this palace would have such grace conferred upon it by God that no one within would grow sick, or hungry, or die on the day they entered.

The father had risen from his sleep terrified but then been reassured by a voice speaking to him in his waking hours, telling him not to hesitate, to do as he had been told and trust that all would be as it had been promised. And apparently it was, complete with crystal flooring, jewels and melted gold for concrete, and a ceiling of sapphire set with topaz that was compared to stars illuminating the heavens. Completing the apparently open-plan layout were golden columns that narrowed to needle points at the ceiling so as to obscure the glimmer of gems on the ceiling as little as possible

Palaces aside, Prester John’s realms contained many strong fortifications, and many of the strongest men and women, with Amazons in particular being mentioned. They contained the strongest armies. Armies that by some accounts numbered among them the people of Gog and Magog, who did not fear death and ate the dead of their enemies. Armies that stormed forth with the priest-king himself sometimes accompanying them, thirteen great crosses of gold born on chariots before him, ten thousand mounted soldiers, and one hundred thousand on foot behind each. Among all this military might, the priest-king himself was unarmed and unornamented. There was a simple wooden cross, and there was a golden vase filled with earth to remind him that this was what his body would return to, but there was also a silver one, this one filled with coins to remind others that he was lord of lords.

“We cannot at present tell you enough about our glory and power,” the letter concluded. “But when you come to us, you will say that we are truly the lord of lords of the whole earth. In the meantime you should know this trifling fact, that our country extends in breadth for four months in one direction, indeed in the other direction no one knows how far our kingdom extends. If you can count the stars in heaven and the sand of the sea, then you can calculate the extent of our kingdom and our power.”

The Epistle of Prester John announced to its readers the presence of a Christian king, one whose power was beyond the reckoning of even the mightiest of emperors, yet one who preferred to be known by the humble title of prester, presbyter, priest. It promised those readers that this powerful lord intended to protect his fellow Christians and with an army of overwhelming numbers and strength to do so, along with those flesh eaters they brought with them, it seemed he was very much able to follow through on that promise, to sweep aside any and all opposition and to conquer the Holy Land. You could see how this might appeal to a certain readership. How it might have made them want to believe. And there were little additions made to some copies of the letter to help this belief along the way.

As mentioned, the text presents itself as a letter to the Byzantine emperor, but how had it reached a Latin readership? One version of the text concludes with a note of explanation, that quote, “Here ends the book or history of Prester John, which was translated from Greek into Latin by Christian, Archbishop of Mainz,” and in some cases there was the additional detail that Christian was, quote, “at that time in Greece, having been sent [there] by the Roman emperor, and he carried [the Letter] with him into the kingdom of the Teutons.” Some observers have since suggested that this Christian of Mainz was perhaps the actual author of the whole thing, but either way, these little touches added believability to the communication of the far-off Prester John.

And where was he? Where was this amazing empire? As I mentioned, there was some connection made to identifiable place-names in present-day Iran and Uzbekistan, and there was also mention that his, quote, “magnificence dominate[d] the three Indias.” So what were those three Indias? North and south India seem clear enough, but what of the third? That could mean a number of different things, like Syrian Edessa, linked to the Prester John story and to India, by its connection to St. Thomas, like southern China, referred to at times as “Upper India” even into the 16th century, or like east Africa. Like the illusive lands of Prester John, the three Indias could be hard to pin down on the map.

So, there we have it. A religious leader from India, a man named John bringing stories of a Christian city and miraculous doings in a mountaintop church, a story of a great victory won by another man who was said to have come just short of bringing his army to Jerusalem, and a letter.

All in all, the epistle of Prester John was quite the calling card. It was full of imagery of seemingly unbelievable creatures, unbelievable wealth, unbelievable power. So, did people believe it? How was it received? How were its contents then used to interpret the widening world that medieval Europeans were becoming aware of? If not based in reality, then what were its sources? If not written or dictated by a nigh on all-powerful Christian king of the east, and indeed it was not, then who wrote it and why? These are some of the questions we’ll get into, not necessarily definitively answer, but get into, as we get into this series. We’ll touch on the different depictions of his realm and how they evolved over time, how a 12th century forgery had life for longer than its writer could possibly have imagined.

Sources:

Otto of Freising, Chronicon, ed. G.H. Pertz, MGH SSRG (Hanover: Hahn, 1867), VII, 33, (pp. 334-35), translated by James Brundage, The Crusades: A Documentary History, (Milwaukee, WI: Marquette University Press, 1962). Accessed at Fordham University Internet Medieval Sourcebook.

Prester John: The Legend and its Sources, compiled and translated by Keagan Brewer. Taylor & Francis, 2019.

Baring-Gould, Sabine. Curious Myths of the Middle Ages. Roberts Brothers, 1867.

Heng, Geraldine. The Invention of Race in the European Middle Ages. Cambridge University Press, 2018.