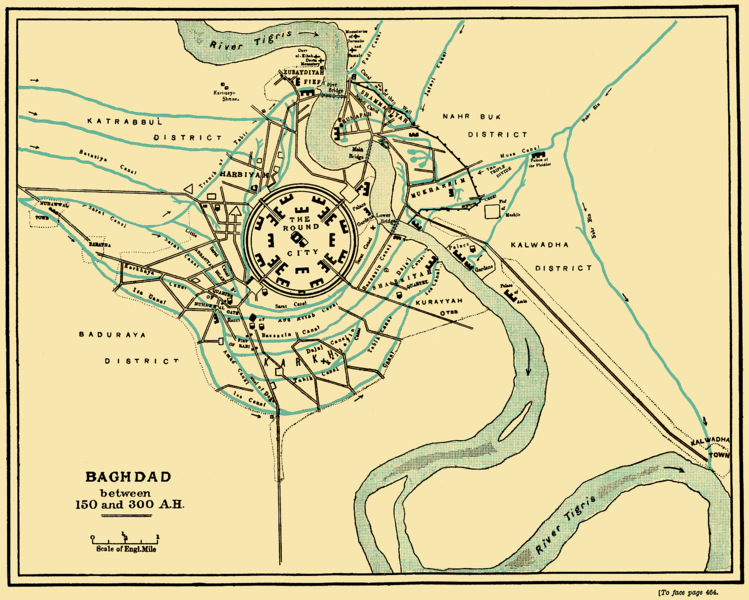

Map of Medieval Baghdad Wikimedia

YOU CAN LISTEN TO THIS EPISODE HERE OR ON YOUR FAVOURITE PODCATCHER.

There’s a story you might know, or kind of know. It goes like this.

A young poet is discovered in the company of a woman, a woman who, most unfortunately for the poet, just happens to be married to a powerful nobleman. He is not killed, so there’s that. But he is sent away. He is sent away into exile from the court of the Caliph of Baghdad, and as something of a justification for banishing him to the wilderness, he is given a job. He is to travel north to the Volga River and act as his caliph’s ambassador to the Bulgars.

The poet’s caravan does not manage to get very far north before it’s waylaid by raiders, but the poet/ambassador escapes death or capture. He is rescued by the appearance of a group of Norsemen who take him back to their settlement. There, he witnesses the funeral of their old king and the crowning of the new one, and there, a request for help is received from the even farther north. Some mysterious evil haunts the land. The king’s aid is needed.

When the wise woman of the village is consulted, she declares that a mission to defeat that evil will succeed, but certain measures must be taken. Thirteen men must go, and one of them must not be a Norseman. All eyes turn to our poet, who is conscripted to go north.

He goes, and he witnesses horrifying events. There is indeed a mysterious evil afoot, materializing out of the mists to snatch up even the strongest of men, taking their heads and leaving blood-drained remains covered in teeth marks. It comes in the night, part bear and part human, and cuts them down in their feasting hall. It comes at dusk as a fiery worm, and it terrorizes the village.

There’s a raid by the poet and his new friends into an underground tunnel system, an absolute horror-show beneath the ground. There’s a struggle against a kind of cult-mother armed with a poisoned claw, a desperate last battle in defence of the village, and the heroic death of the king. After that, it’s time for one last royal funeral, and for the poet, safely back in his homeland to record all he had seen in his time in the north.

The story, which you might have recognized, is that of the late 90s movie, The 13th Warrior. It’s based on Michael Crichton’s novel, Eaters of the Dead, and there’s no small amount of Beowulf to it, but there’s another source too.

That poet from the court of Baghdad, the one flung into violent adventures in the north, and played in the film by Antonio Banderas, that was none other than 10th-century Arab traveller Ahmad ibn Fadlan, and this, this is his story.

Hello, and welcome. My name is Devon, and this is Human Circus: Journeys in the Medieval World, the history podcast that follows the stories of the medieval period’s most interesting travellers. If you are enjoying the podcast, and it’s an option for you, you can express your enjoyment via patreon.com/humancircus where you can also access ad-free episodes and bonus endings, and where I’ve started to post the odd written follow-up on topics that interest me. And I want to send out my gratitude to Ethan for joining the Patreon and doing just that. Thank you very much!

Now, to the story.

As you heard a moment ago, we are back on track with historical travellers after our brief wanderings in the woods with outlaws last episode, and as you also heard, the subject here is one Ahmad ibn Fadlan. I should say from the top that his story isn’t actually much like the movie 13th Warrior. There’s no Antonio Banderas, no underground horror-shows, no repeated jokes about Arabs having small horses and being unable to swing full-sized swords, though such teasing is not actually so very far from the source. Ibn Fadlan is not an exile, dispatched in disgrace to go among some poorly understood northern barbarians. He is not, in fact, a warrior at all, whether 13th or otherwise. But he does have his own fascinating story. He did go among peoples that were deeply unfamiliar to him and tell us, his readers, about them in an eyewitness account. He did, most famously, encounter Viking traders on the rivers of the Rus and describe a ship burial.

Our ibn Fadlan was in perfectly acceptable standing with his caliph al-Muqtadir, and he was not sent away to disappear. He was part of a diplomatic mission formed to answer the petition of a Bulghar king, and his telling is introduced like this:

“This is the written account of Ahmad ibn Fadlan ibn al-’Abbas ibn Rashid ibn Hammad, the envoy of al-Muqtadir to the king of the Saqalibah. [That would be a word in the Arabic sources for Slavs] His patron was Muhammad ibn Sulayman. It records his observations in the realm of the Turks, the Khazars, the Rus, the Saqalibah, the Bashghird, and other peoples. It also includes reports of their various customs and ways of living, their kings, and many other related matters, too.”

Some time in the year 920, or early in 921, a lord of the Volga Bulghars named Almis Iltibar had sent to Baghdad with requests. He had come to Islam and wished to offer himself and be accepted as an emir to the caliph, to have the caliph’s name spoken from the pulpit. He asked for experts to be sent to instruct his people in the law and in proper religious practice. More materially, he asked for money to be sent so that he might build a mosque and also a fort to defy his enemies. He wanted the caliph for a patron, and it’s hard to say which of the requested elements was more important.

But let’s consider why this mission was dispatched. It’s not hard to see why the Bulghars would make such a request, because, who wouldn’t want a powerful friend and money with which to ward off one’s foes? It’s not hard to see why Almis might have sought independence from the Khazars, to free himself from local vassalage through attachment to another, greater, power. It’s entirely understandable for someone to request resources and religious instruction. But what was in it for the other party involved? What was going on in Baghdad? Let’s spend a moment there.

The context of the ibn Fadlan mission is the Abbasid Caliphate of Abu’l-Faḍl Jaʿfar ibn Ahmad al-Muʿtaḍid, or as he’s more commonly referred to, al-Muqtadir, the omnipotent. Al-Muqtadir had ascended to the throne in 908, at only 13 years of age, and would reign, with one brief, rebellious interruption that put his brother in power, all the way to 932. But that didn’t mean his time in power, lengthy as it was, was marked by towering success. Quite the contrary, it’s remembered more for a faltering hold on centralized power, a steady emptying of the treasury, violent religious clashes, and a rotating door at the vizierate where one man after another was replaced and their holdings confiscated. That last part will show up as instrumental in this story.

Baghdad was, as James E. Montgomery puts it, “a city on the brink of lawlessness and anarchy. It was poorly managed, food supplies were unreliable, famine was a regular occurrence, and prices were high. There were sporadic outbreaks of disease, largely because of the floods occasioned by municipal neglect of the irrigation system.”

But we shouldn’t look at this like it’s some backwater, regional trading post. it was also an imperial capital, one of the world’s great cities, maybe, at that time, its great city, a centre of trade and culture, of religious and intellectual life, and of power, a hub into which flowed goods and ideas from all the known world over. It was marked by extreme wealth and by spending in abundance, according to Montgomery, “the world’s largest consumer of luxury goods.” Consider for example this description of the Arboreal Mansion, there in Baghdad’s palace complex. And this description is also taken, one last time, from Montgomery’s introduction to my main source here, the 2017 Mission to the Volga.

Quote:

“This mansion housed a tree of eighteen branches of silver and gold standing in a pond of limpid water. Birds of gold and silver, small and large, perched on the twigs. The branches would move, and their leaves would move as if stirred by the wind. The birds would tweet, whistle, and coo. On either side of the mansion were arranged fifteen automata, knights on horseback, who performed a cavalry maneuver. The lavishness of this craftsmanship and the ingenuity of its engineering match the opulence of the caliphal architectural expenditure for which al-Muqtadir was rightly famed. The Arboreal Mansion was just one of the many awe-inspiring sights of the caliphal complex (which included a zoo, a lion house, and an elephant enclosure) on the left bank of the Tigris: one observer reckoned it to be the size of the town of Shiraz.”

It’s easy to see how even the healthiest of treasuries might have started to run dry under the weight of such spending. And it’s pretty clear that there was no shortage of appetite to spend it close to home. But what about further afield, out there on the Volga? Why that?

One potential answer is trade. As we’ve seen many times in these stories of trade and diplomacy, the two were then, as now, often very tightly intertwined. In this case, the Volga region was a substantial source for furs, slaves, wax, amber, and honey and its people had a substantial appetite for silver dirhams, an appetite very much in evidence in the great many found in Viking coin hoards since. The fortifications Almis wanted built might have provided a stronghold from which to control trade in the region and protect it from the Khazars. It might have been an attempt to economically bypass the Samanids of today’s Iran and Afghanistan, or, as others have suggested, it may have been a joint venture with the Samanids. Perhaps the Samanids sought aid in dealing with their Turkic neighbours to the north.

Or maybe the mission was more religious in nature. It was a tumultuous time, as ever, and there was many a divergent strain of belief, a competing idea, or quote/unquote heresy that the authorities in Baghdad would have wanted to contain. From Qarmatian to Zoroastrian, there were many schools of thought they would not have wanted taking hold among the peoples along the Volga.

And of course one cannot ignore the simple power of flattery and the flattery of power. Here was a ruler writing to the caliph to offer himself and his people in a kind of submission, saying in effect, “you are our lord,” and offering to proclaim it in their prayers. It was an offer few would refuse.

I’m sure all these factors were to some degree present in the decision to send ibn Fadlan and his fellow travellers.

And who were those fellow travellers? Who, for that matter, was ibn Fadlan? As is common in these narratives, we don’t have a lot of detail. As noted in the edition I’m reading, he was not an “Arab merchant, or the leader of the mission, or [its secretary], or a jurist.” But he was an educated man, a person chosen to observe protocol, to read letters, and to present gifts, a person able to offer instruction in Islamic law.

There is, aside from ibn Fadlan, an interpreter, probably more than one. There are soldiers, though they don’t all make the whole trip. There are jurists and instructors; the Bulghar king had asked for those. There’s a representative of that king. There’s the person in charge of the entire embassy, though he does not come along himself, and there’s a freed man bound to him, an envoy named Sawsan al-Rassi who does.

In this company, ibn Fadlan was going to make a 4,800 km journey to his destination, a journey that would last 325 days and range from desert heat to frozen river cold, cold that we’re going to be hearing quite a bit about. He was going to find himself in situations that were decidedly less grand than that arboreal mansion, walk new paths, face new dangers, and be confronted by the alarming strangeness of the people who now surrounded him. Like Brancacci last episode, he would find himself a stranger in a strange land. Like Brancacci, he would not always be comfortable. And like Brancacci, he would find himself and his mission underfunded for success.

“We travelled from Baghdad, City of Peace,” the account reads, “on Thursday, the twelfth of Safar, 309,” or June 21st, 921 CE.

They rode northeast, stopping at Nahrawan for a day, and then al-Daskarah for three. It was two at Hulwan, two at Qirmisin, current Kermanshah, and Hamadhan for three. All of these locations were relatively close to home and clearly not worth commenting on, but still there were threats. Moving across northern Iran, they had a chance encounter with an ibn Qarin, agent of the hostile Ziyarid dynasty, and had to conceal their identity as they hurried on to Nishapur. There, they’d hear that a Ziyarid governor had been killed. Danger had not touched their caravan, but it was out there as they travelled on to Merv.

The party spent three days in Qushmahan, at the edges of the desert. Ibn Fadlan reports that they changed camels in preparation for the desert ahead, but maybe they also sampled the raisins the place was apparently famous for, visited its mosque or its markets, or walked along the great canal that watered its orchards.

They were heading next for Bukhara, and we’ll join them there. But first, a quick break.

…

The Bukhara that ibn Fadlan was arriving in was that of the Samanids, an enormously powerful dynasty that for slightly more than one hundred years had ruled over increasing portions of present-day Afghanistan, Uzbekistan, and Iran. It was the Samanid capital, rich in silver from their many mines and enjoying the fruits of their highly developed agriculture and the presence of the quote/unquote “founder of Persian poetry,” Rudaki, along many other leading lights in culture and science. It was soon to enjoy a very pleasant period of consolidation and stability, a real high point that some people point to as the high point of the Samanid dynasty.

Ibn Fadlan and co. were catching Bukhara with the right ruler, the emir who would oversee all of this, but Nasr II hadn’t quite yet become that ruler. He was still extremely young, “still a boy,” we read in ibn Fadlan’s report, and not yet with a beard. Nasr II was not much more than 15 years old and already 7 years into his reign, having come to power with his father’s 914 assassination.

They met with the emir’s chancellor, who set them up with a residence and with someone to see to their needs. He arranged an audience, and that’s where the mission’s money troubles started to rear their head.

The issue was with how the whole thing was meant to be paid for. They hadn’t just been handed a sack of silver and told to go present it to their new Bulghar friends. Instead, they’d been given something more like an idea as to how it could be paid for. A source of funding had been identified to cover the costs of the venture, but at that audience, problems with that source had begun to become apparent.

It all started well enough. They were cordially welcomed by the young Nasr II who directed them to sit.

“How was my patron, the Commander of the Faithful, when you left him?” he asked, referring to the caliph in Baghdad. “May God give him long life and cherish him, his retinue, and his spiritual companions.”

“He was well,” they replied.

And then they read him the instructions of the caliph.

He was to provide them with a letter to his governor in Khwarazm, with orders not to hinder them on their way. He was to give them a letter to the garrison at an outpost named Zamjan Rabat, the Gate of Turks, where they were to be given an escort and be aided on their way. And then there was the matter of money. That was to come from an estate named Arthakhushmithan, described as a substantial city of busy markets. Its revenues were to be entrusted to a man named Ahmad ibn Musa Khwarazmi, and he should then dispense the money they would need.

Great, the emir might have said, looking around the room questioningly, and where was this Ahmad ibn Musa?

And that was the problem, though the travellers didn’t know it yet. They just said what they knew, that ibn Musa would be along shortly. He’d left Baghdad behind them, for some reason had been set to leave four days later, so they would just need to wait, and wait they did. And wait. And wait some more. Where was Ahmad?

The answer to this question lay with the estate that was to pay for it all. It was to be given to Ahmad ibn Musa, but of course it was to be given to him from someone, and that someone was Abu’l-Hasan Ali ibn al-Furat, a member of a powerful family that would, over two centuries, fill many important offices within the Abbasid Caliphate, and a man who would, by the time he was done, have been a three-time vizier to al-Muqtadir.

Here in this story, we’re catching him in one of his out-of-power interims, this one spent imprisoned in the palace. He’d been removed from power once back in 912, after a reign of absolute dominance during which he’d engaged freely in enriching himself. He’d gotten back in the door in 917, but then, only the year after that, he’d misstepped again. He was back out of office and into confinement, still there here in our story.

He would return. He would become vizier again in 923, and he would use that power to lash out at anyone who had ever offended him. But that was for the future. For now, it was one of his properties that was being parcelled out to pay for this endeavour, his estate that Ahmad ibn Musa was on his way to collect. And Ali ibn al-Furat may have been on the downswing in his perpetual struggle over control of vizierate, but that didn’t mean he was going to part easily with what was his. It was ibn al-Furat’s agent, al-Fadl ibn Musa al-Nasrani, who was to provide Ahmad ibn Musa with means to pay, but as we’ll see, either to protect ibn al-Furat’s interests or his own, he would chose a different path.

In Bukhara, ibn Fadlan and his colleagues waited for a full 28 days for the man who had supposedly been only 4 behind them. Some among the party spoke with increasing concern of the coming of winter and how it would affect their journey if they were delayed any further. Ibn Musa, they insisted, would simply catch up to them further up the road, and al-Furat’s agent helpfully encouraged them in this, agreeing heartily that yes, the onset of winter was a cause for worry, and no, it would not be a problem at all for ibn Musa to follow them with the money.

After 28 days, ibn Fadlan and the rest left Bukhara without ibn Musa and without the money. They travelled now along the river, going by hired boat, and forced by the cold to make camp earlier than they would have liked on the way to Khwarazm. They could not last a full day exposed to the elements.

At Khwarazm, ibn Fadlan continued his assessment of local currency, particularly the state of the dirham. Back at Bukhara, he’d written of dirham of different colours than he was used to, of different types of yellow and red brass. Here, he said they should not be accepted at all, being as they were too adulterated with brass and lead.

He wrote of money lenders who dealt in dirhams sheep bones, and spinning tops. “They are the strangest people in the way they talk and behave,” he said. “They sound just like starlings calling.” A day’s journey on from there was a village where he said their speech sounded like frogs croaking. Things would get quite a bit stranger for him than that.

As at Bukhara, they were well received by the emir of Khwarazm, given a warm reception and a place to stay, but also like at Bukhara, there were problems. They were called in after three days by an apparently highly concerned emir who saw the whole thing as a dangerous ploy on the part of a particular soldier who travelled with them, a man who, the emir said, had previously sold iron in the land of the infidels. He was, it seems, being accused here of engineering more trade of that sort. Besides, there were, quote, “a thousand infidel tribes in [their] path,” and the emir could not allow them to risk their lives. He sounded absolutely adamant in his concern for their safety, but maybe something else he mentioned, that it ought to have been the emir of Khurasan who had the caliph’s name proclaimed out there where they were going, had something to do with it. Maybe that, more than their well-being, was why he insisted he should detain them there and write to the caliph.

In any case, they did eventually extricate themselves from the overly helpful emir. They did have that letter of instruction from the caliph. They made their exits and sailed downriver to al-Jurjaniyyah, and here, no emir kept them, but it didn’t matter. They had already been kept too long.

The river Amu Darya froze over, its span sufficiently hardened to bear horses and carts without complaint. The season brought snow and “wild, howling blizzard[s]” down on deserted streets. It brought cold intense enough that even containers wrapped in sheepskin cracked, even ancient trees split, even the ground itself opened up. It brought cold enough that got to him even smothered in skins and pelts, within a felt yurt that was set up, though the wording is somewhat confusing, in a chamber within another chamber. It was enough that ibn Fadlan would sometimes wake up with his cheek frozen to the pillow, enough that after going to the bath house, he returned to find his beard a block of ice that needed to be thawed by the fire, and enough that he and his companions thought the place an icy “portal to the depths of hell.”

On a less somber note, he wrote that the people did have access to cheap and plentiful wood. When they were generous, they would say “Come to my house so we can talk, for I have a good fire burning.” And those in need, did not wait at the door, but came in to warm themselves by the flames before asking for food.

Still, one day he heard that two men had taken their twelve camels to fetch firewood from a forest, but they’d forgotten their flint and tinder boxes. By morning, all fourteen had been frozen to death.

By February, the season changed, and the river at last melted, allowing the travellers to think about moving on, to set about acquiring provisions. They got Turkish camels for the way ahead, and made camel-skin rafts for river crossings, though not, I think, from the camels they’d just purchased. They packed millet, bread, cured meat enough for three months, and they were warned about the cold.

They’d just been through absolutely infernal temperatures, by their reckoning, but this, they were assured, had been nothing. They were told terrifying stories and urged to take the matter seriously, so when they left, they did so each in quote, “a tunic, a caftan, a sheepskin, a horse blanket, and a burnoose with only [their] eyes showing, a pair of trousers, another pair of lined trousers, leggings, and a pair of animal skin boots with yet another pair on top of them.” Once mounted on their camels, they were so ensconced in clothes that they could scarcely move.

It was still not going to prove to be enough for comfort, but at least they would be leaving as well prepared as they could be. What they wouldn’t have with them were those jurists and instructors. By this time in the story it is only one jurist and one instructor, the reduced number either the result of an error here or earlier, or because the others had already fled, but however many they had been, they were taking the Bulghar king’s wishes for instruction back to Baghdad with them, along with the retainers who had travelled with the party thus far.

The other thing the party was going without was that money, and ibn Fadlan was pretty worried about that. He claims to have said as much to his fellow travellers on the day they set off from al-Jurjaniyyah.

“The king’s man accompanies you,” he told them. “He knows everything. And you carry the letters of the caliph. They must surely mention the four thousand dinars intended for the king, … and he will demand that you pay this sum.”

The concerns seemed well founded, but his companions apparently didn’t think so.

“Don’t worry about it,” they said. “He will not ask us for them.”

But ibn Fadlan was not reassured.

“He will demand that you produce them,” he replied. “I know it.”

Very likely the time had long since past when he and the others had looked in hope for the coming of ibn Musa and the money, and indeed there was no cause for hope. Though they couldn’t have known it then, that had been put to rest before they’d even left Bukhara.

That representative of Ibn al-Furat the fallen vizier, had heard how he was to hand over the estate to ibn Musa, and he’d written to certain officers along the way with ibn Musa’s name and description, instructions to send out spies, to search for him in every caravanserai and lookout post, and when they found him, to hold him and to not to let him go until they received orders for his punishment in writing.

Perhaps he was entirely unaware of these circumstances, or maybe he knew full well that ibn al-Furat would not lightly release his hold on his wealth and took what precautions he could, but either way, ibn Musa only made it as far as Merv before being seized and chained.

Those four thousand dinars were decidedly not coming, and despite all his concerns as to how they would be received without them, ibn Fadlan and the rest of the group that remained were just going to have to do without. They hired a local guide, and that Gregorian Monday of March 4th, 922, they left al-Jurjaniyyah, stopping briefly at the outpost at the Gate of the Turks. By the following morning, the weather had gotten even worse.

They were at a trading post where snow up to their camels’ knees would keep them for 2 days. And then, they quote “plunged deep into the realm of the Turks through a barren, mountainless desert. [They] met no one. They crossed for ten days. [Their] bodies suffered terrible injuries. [They] were exhausted. The cold was biting, the snowstorms never-ending.”

The conditions were severe enough that they made what they’d previously suffered, those ice-block beards and cheeks frozen to the pillow, feel like summer, bad enough that they felt willing to give up and die. But of course they did not do that. They had quite a ways to go just yet, and the hardships were just beginning.

...

One day, when the cold was particularly fierce, one particularly excruciating day among many pretty excruciating days, Takin, the soldier/translator who rode with ibn Fadlan, laughed and turned to him. He’d been speaking in Turkic to the man next to him, and now he told ibn Fadlan what they’d been talking about.

“The Turk,” he said, gesturing to the other man. “The Turk wants to know why God is doing this. What does our Lord want from us? He is killing us with this cold. If we knew what He wanted, then we could just give it to him.”

It was a difficult question, one might have thought, but then ibn Fadlan had an answer.

“Tell him,” he responded, “that He wants you to declare ‘there is no god but God.’”

At this, the Turk laughed and replied, “Well, if we knew Him, we’d do it.” Or, as I’ve seen it written elsewhere, “If we had been taught how to say this, we would say it.”

The caravan would continue on, and find a good place to stop with plenty of wood to burn, where they could dry their clothes in the fire’s heat. They would journey on, but we’ll be pausing here for now.

Next episode, we will be joining ibn Fadlan on the continuation of his trip north, hindered as it might be by extreme weather and lack of funds, and we’ll look through his eyes at people and places unfamiliar, practices that may have seemed to him unnatural.

If you’re listening on the Patreon friars’ feed, then please do keep listening for a 10th century picture of central Europe and evidence of its trading connections with, among others, the Samanids. But whether you are or not, thank you very much for stopping by. I hope you enjoyed listening to this, part one of ibn Fadlan’s story. I’ll see you soon for part two.