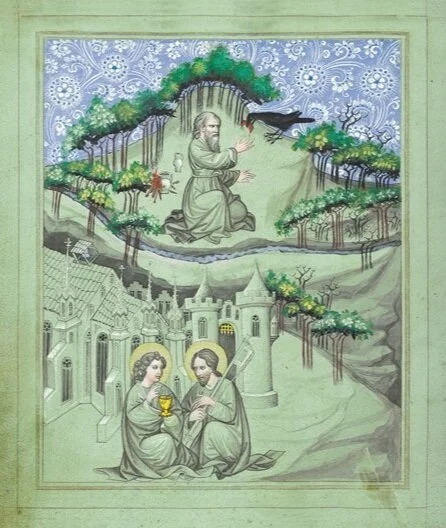

The Travels of Sir John Mandeville - British Library Add. Ms 24189

This is the script for a podcast episode you can listen to here or on your usual podcast app.

So far with Mandeville, we’ve talked a little of his possible identity and to what extent he himself actually travelled at all - Was he at least one of the many who made their way to Jerusalem on pilgrimage? Or did he only have access to those who did, in written form or perhaps even, in some cases, in conversation. We’ve covered the text’s treatment of Constantinople, the Holy Land, and Egypt. We’ve been to India, “Greater India” denoting a vast stretch of possibilities from Iran to Indonesia. We’ve talked of the treatment of other religions and also of those Plinian peoples, those hybrid creatures or monstrous races, not for the first time on this podcast, probably not the last time either. The Mandeville writer notes that “[many people have a great liking to speak of strange things,]” of marvels, monsters, and miracles, and little has changed in that regard. That “great liking” would not go away, really hasn’t ever since.

It’s been argued, by Jeffrey Cohen for example, that monsters are critical to understanding culture, to locating it at its extremes and finding meaning there. Last episode, we touched on what meaning we might find in this case, what meaning Mandeville found and might have expected of his readers, and it’s worth noting that the author does not always seem to be entirely certain of that himself. He was sure that the marvels, miracles, and monsters God had worked ought to be made known as testimonies to his might, in the text argued that such was the case with a monk at the monastery of St Catherine. And elsewhere, he was certain that a shoal of fish offering themselves up on the beach to the king of that land was indeed a great signifier but less so as to what it actually signified.

In the section we’re entering here, we haven’t entirely left behind the hybrids, the marvels, not all of them monsters. We’ll find a gourd-like fruit growing in “a very large country” between Cathay and India that was cut open to reveal a kind of animal within, “a little lamb without wool,” that people would eat, both enclosing fruit and inner meat. We’ll find Mandeville arguing with those he heard this from that it was indeed wondrous, but only in an entry-level kind of way, not so much as the barnacle goose back where he lived, a tree fruit that would become a flying bird and was, he said, quite delicious.

Odd to find this outburst of regional pride regarding such things. Odd to find that in other medieval sources this barnacle goose is written of as being unique to the Kentish coast near Faversham. But so it goes.

In this episode, we’re headed for China and for the court of the Mongol Khans, the home of the Yuan Emperors, though, as was the case in Egypt, we’ll find them somewhat adrift in time. We’ll explore some of the surrounding regions the text danced across, and their stories, and with this last episode on Mandeville, we’ll explore something of the impact of the text.

Hello and welcome. My name is Devon, and this is Human Circus: Journeys in the Medieval World, the podcast covering medieval history through the travellers that journeyed through it. And in light of the context of what’s happening as I’m recording this, what’s been happening for quite a while now maybe, depending on where and when you are, I want to take this moment to wish all of you who are listening well in pretty trying times. This is a medieval history podcast - I’m not exactly covering current events here - but at the same time it feels a little ridiculous to not mention something that pretty much everyone is affected by or has been over the last number of months. On a personal note, I’ve been so far, so good, barring some lost work while the company I work for sorts out what it’s doing and how, and I hope you and your friends and families are also keeping healthy and relatively happy, that you’re looking after yourselves and each other, and I hope you enjoy this bit of 14th century escapism.

And now, back to the story. We pick it up in China.

The text introduces southern China to us as “the best region in India, the most pleasing and most bountiful in all things within man’s power,” a place you travel many days east on the Indian Ocean to reach, a land of 2,000 cities and many more towns where no one goes begging. A nice place.

There’s one city, “larger even than Paris” we read, with a fine waterway, with birds twice as large as are found anywhere else, and people who enjoy eating nothing more than snakes. Give a luxurious banquet in this city but offer no snake, and your guests will offer you no gratitude in return.

Another city, home, as Mandeville notes, to a small number of Christian friars, is larger still, at “fifty miles in circumference,” the largest in the world, with twelve gates out. It’s through one of them that we’ll pass to reach the monastery.

There, in “a monastic abbey, a little way from the city,” we find a garden large and beautiful, abundant with fruit trees, and home to a variety of different apes and other creatures. If we wait until the monks finish their meal, we’ll see one of their number bring the leftovers out into the garden and ring a small silver bell. Then, all the gardens’ animals, three or four thousand Mandeville says, come out and form ordered lines. They’re fed from a silver vessel, and when they’ve finished, the bell rings again and they all disperse, making their way back where they came from.

Obviously, the numbers are a little too much to take. I mean, how large is this garden supposed to be that it can hold three or four thousand baboons and sundry other creatures? And then how large is that silver vessel supposed to be that it can feed them all? And how absurdly strong is that monk that he can carry it out to them? But there’s more to the story than that.

When our narrator asks a monk why they do it, he replies that the animals have the transmigrated souls of human beings now dead, that the gentler and more attractive ones were from nobles and aristocrats, the uglier from base commoners, naturally. What we’re looking at here is reincarnation, and our 14th-century Christian guide seems to take it in stride. Alright, he says, but wouldn’t it be better to give the food to those souls who are still human now? To the poor? The answer: there simply are no poor here. No poor, and one grand city after another. Overall, the place gets a glowing review.

From the Buddhist monastery near Hangzhou, what Mandeville calls Cassay, with its souls doing penance, it’s six days to Chibence, our Nanjing, with its twenty miles of formidable walls and its sixty fine bridges, sometimes numbered instead at three hundred and sixty.

You travel on, crossing a great river, nearly four miles in width, its fresh waters snaking through Pygmieland, home to an attractive people growing less than three feet high and living only eight short years. None of these folk labour in their own land. Rather, they quote “keep big people like us amongst them to work for them and they hold those people in such scorn as we would if we had giants among us,” giants, though they also played other roles in medieval literature, often being the club wielding eaters of human-flesh, the figures of power from before or beyond the human realms whose heads must be taken by the chivalric knight.

From Pygmieland, one travelled through many towns and cities until one came to the one where many large ships were built, “white as snow” due to the wood they were made of and laid out like large houses with their rooms, chambers, and halls. You left there by the river along which goods and merchants travelled, and in time you came to an ancient city and alongside it, constructed by the Mongols, that of Cadom, the name perhaps derived from the Anglo-French Caydo, itself an approximation of Daidu, the city also known to the Mongols as Khanbaliq, the “city of the Khan,” and more recently to everyone else as Beijing. You, through the eyes of Odoric, mediated by the Mandeville author, and then also by transcription and then translation, had finally reached the Mongol capital and heart of the Yuan Dynasty’s empire. And what did it look like?

Two cities, the old and the new, twenty miles across, and in the new, the palace. Mostly, we see the palace. Around it are walls an unlikely two miles high and within a garden large enough to feature a fine mountain and fruit-bearing trees of all kinds, a moat and other water features well stocked with fish, fowl, and wild creatures, so that the khan may go hunting in his preserve whenever he pleases.

Of the palace itself, we see its halls luxuriously decorated, walls covered in panthers’ pelts as red as blood and pleasantly scented, shining in the light and framed by golden columns. At the palace’s centre, the Great Khan’s dais, all in pearls and precious gems, golden serpents at its corners, and below it fountains of his drink. In his chamber and atop a golden pillar there is a ruby, a full foot across, that illuminates the room in darkness. And then at the end of the great hall, his throne, raised high and reached by jewelled steps, with a golden edged table before it to eat from, and flour clerks below it to record his words whether they be good or bad. Next to his seat, lower and a little to left, his first wife’s seat in golden edged jasper, and below and to the left of that the second’s, and then lower still, the third’s, and then the other royal women seated as their status determines. On the right, the first son and heir, then the second or some other royal kinsman, and so on.

When they feast, they do so beneath a golden vine complete with branches and grapes, their bunches in red of ruby, white of crystal, yellow of topaz, and green of emerald, the gems mirrored below by those set into the cups and vessels from which the nobility drink and eat. All manner of expensive materials are put to use in their making, leaving only silver which they hold in low esteem and incorporate only on the floor or the occasional pillar.

Musicians come forth and perform, and knights in incredible armour crashing against one another. Then, animal handlers bring lions and leopards, birds and serpents, even these things of the wild worshiping and obeying their lord, and then other entertainers, workers of great spectacles, magicians we’d call them, who cause the sun and the moon to appear or disappear, as if even these stars and structures of the sky yield willingly to the khan of khans.

All in all, it paints a picture which, I’m sure you’ve gathered, is one of magnificence, grandeur, and great wealth, and the Mandeville Mongol material that it’s made of is a blend of different sources. We’ve got Hayton the Armenian, a man of political and military experience who in later life became a monk; we’ve got Oderic, who we’ve mentioned a few times on the series; and we’ve got another familiar figure from an earlier series in Friar Giovanni da Pian del Carpine, his account here filtered through to us via Vincent of Beauvais, the 13th-century encyclopedist or compiler.

Taken together, the resultant collage shows us the Great Khan parading from his winter palace, which we’ve already encountered, to his summer one. Xanadu, the text calls it, as Coleridge would, Shangdu, if you’re looking it up later.

We see the khan borne on a four-wheeled chariot in a chamber of gold-panelled aloe-wood, powerful nobles riding beside as escort, and, rather less believably, “four elephants and four stallions go inside,” presumably a bit of distortion that’s occurred over time from the animals going alongside the vehicle. As the party travels through the khan’s twelve provinces, their people set fires before their homes, casting fragrant spices and incense into the flames for the khan’s enjoyment. And which khan is this? As with the situation in Egypt, the issue of when this all is, is really a forceful reminder of the nature of this text.

The story here starts from the beginning. It starts etymologically, looking to the Biblical Ham, son of Noah. After the flood, his brother Shem had taken Africa, Japheth Europe, and Ham, he had been granted Asia. On account of ruling those same lands as Ham, the ruler of the Mongol and then Yuan Empire was called Khan. Or so this highly suspect etymology went.

The origin story carries forward from there, now providing a more recent history even if one we cannot entirely accept. It tells of an old man of very modest means, named Chaungwise, who lies in bed and is visited by a knight, dressed all in white and riding a white horse. The stranger brings with him the message that God has willed that he, Chaungwise, unite the seven tribes, become their emperor, and subject all the surrounding lands to his rule, that is, that of Chaungwise, born Temujin and better known as Genghis Khan.

The next day, Genghis tells the seven tribes, and of course they’re not immediately enthused; they need convincing. But then the white-clad knight returns, and he does so. The tribes make Genghis emperor, and he makes statutes and laws; he commands total obedience, even testing it by ordering people to bring in and behead their own eldest sons, and then he leads them in conquest, first in those nearby lands, and then, after that, at the urging of the knight dressed in white, on past a great mountain and into Cathay. Only then, after his successes there, does he die. His brother goes on to wield power after him, expanding into Russia and further west, but the greater power still is in Cathay, there held by the man introduced in the text like this.

“He calls himself the ruler of the entire world in the letters he sends, ... describes himself as … ‘Khan, God’s son, emperor over all those who work the land and ruler of all rulers.’ … the words around his great seal that he sends say … ‘God in Heaven, Khan on earth, the strength of his seal, the Emperor of all men.’”

And who was this, this ruler of rulers? The author tells us that when he was there it was Guyuk Khan, a name he gets from Carpine, but then Carpine was travelling in the 1240s; that was when Guyuk was ruling and certainly not doing so from present day Beijing. Mandeville also claims to have seen that Yuan palace during a truce between the khan and his neighbours to his south, the truce seemingly a reference to the conflicts which Odoric had been in China for. Mandeville, remember, was supposed to have set sail in 1332, and such is the odd historical setting of the text: naming Guyuk as khan while describing circumstances reported by the later Oderic, a Chinese Mongol capital in the reign of Kublai Khan’s great grandson, nearly a century later. Everything in Mandeville happens all at once.

Despite what I’ve covered so far, the Mandeville material is not all about rulers and their realms, their golden accoutrements, their accomplishments at arms, their, quote, “tru[e belief] in God who created everything, though they still have gold and silver idols to whom they offer the first milk from their animals.” Thanks to his sources, the author had other things to say too.

There’s the law against the spilling of milk or other beverages, and against urinating in the tent, the latter answerable with death - a reminder of how the friars who went among the Mongols struggled with the unfamiliar taboos and regulations, often making missteps and occasionally escaping execution only through being allowed to plead ignorance. There’s the way gifts for the khan are brought between fires to purify them, and if you’ve listened to my earlier Mongols series, you’ll know that anything allowed to fall in the process was judged impure, a poison or other source of harm, and dealt with accordingly.

There are notes on diet, on the happy consumption of everything from rodent to lion, from mare’s milk to mead, on the heavy use of olive oil for its medicinal qualities. And all that courtly splendour we saw is only slightly diminished by the specifics around dining that are found somewhat wanting, the taking of food and drink less than dignified, the chosen meats unfamiliar, the manners a little too reliant on wiping greasy hands on shirts, the meal coming only once a day, the milk coming “from all sorts of animals,” which, from the context, was clearly a bad thing.

In this text, which combined many perspectives mediated under one pen, it’s the culinary culture that suffers critique, that and the Mongols’ dishonesty, their utter inability to keep a promise, but this isn’t purely a case of celebrating material greatness on the one hand while implying unadulterated barbarism on the other.

The text shows us scholars in the khan’s presence with wonderfully crafted astrolabes, clocks, and “other instruments of their scientific pursuits.” We see people who the writer terms philosophers, which is not unfair, but the additional details that they practise geometry, astronomy, pyromancy, and necromancy give us a better understanding of what that might mean, as does the claim that nobody around the khan does anything without their word, just as nobody anywhere can initiate war against him without their knowing of it immediately.

There are physicians too, two hundred Saracens and two hundred Christians, and these Christians are not the only ones here. There are many converts at court though many of those will not identify themselves as such, and our guide asserts that even if the khan and his men are unchristened, they quote, “do indeed believe in God Almighty.” A point that someone was very intent on making, and one which he repeats again elsewhere. “Even though they are not Christian men,” he writes, “nevertheless the Emperor and the [Mongols] believe in God Almighty.” He talks of how these were people who had, quote, “some of the articles of our faith.” True, they had divergent beliefs and laws, but they also all had some element of Christian ideas there.

They believed in a God of Nature, a creator who all humans must fear and serve. They just couldn’t speak of that god correctly and couldn't avoid the pitfalls of the evil angels that spoke to them through their idols. But still, the author contended, they had the correct elements there of Christian belief, those they’d reached through intelligence rather than teaching.

And continuing with that theme, we see Christian practitioners come forth when the khan travels. They bear crucifixes and holy water and sing the hymn “Veni Creator Spiritus” as they approach. He pauses for them, receives their blessings and from their chief priest, prayers, fruits, and a golden platter as gifts. And those Christian clerics who live near his son or his wife do the same, participating in the curious religious economy of the Christian-Mongol world that I covered more of in my Mongols series.

And continuing with the unavoidable thread of then-recent history, we of course read of their prowess in battle, their cleverness, and the absolute folly of giving chase when the Mongols fled, for they could shoot behind them just as easily as they could kill those before them. The Mongols’ success with false-flight had made for a hard-won lesson but was by this point very solidly established. Even if the text doesn’t quite explain all that they might do with that opportunity, “don’t chase Mongols,” was a pretty solid principle to go by, and a good basic truth about the Mongols on which to part from them.

After this break, we will part from them. We’ll explore the world around them a little, and I’ll talk a bit more about the Mandeville text and its legacy.

...

As we saw a little of last episode, Mandeville’s world was a weird and wonderful one, and our ever untrustworthy guide, heading south from Greater India and its islands with his exact position somewhat up in the air, started to sketch out its workings.

He said that as he sailed south, he could no longer see the Tramontana Star, the North Star by which sailors were guided, for it wasn’t visible so far south. But its opposite, the Antarctic, that very much was, and the two stars between them divided the firmament.

Our guide provides astrolabe readings in Bohemia, Libya, and elsewhere. He attests by observation of the stars and by anecdote that the world is a sphere, and that if he had but a fleet and following, he could travel round it, finding everywhere people, nations, and islands. He recalls a story, one that he says he had heard when he was young, of a brave man who went out for a time to see the world, who went so far as India and its 5,000 islands, and then simply carried on, carried on by land and by sea, going such a great distance that he eventually came to an island where the people, to his very great surprise, spoke in a language which he recognized; they herded cattle using words which he knew. How was it possible?

Of course, he had again reached his own country, or rather very nearly so. And then the story continues, has him turning around and going all the way back the other way. It’s only on a later voyage when stormy seas near Norway sweep him to shore that he thinks he has again found the island he’d landed at before, notices that same language being spoken in the same way.

In Mandeville, there’s no real conclusion as to whether this world traveller entirely gets it, but it is an intriguing illustration of a round Earth and medieval writers’ knowledge of it, despite statements to the contrary that one still sometimes sees. And how did they know it? Not just anecdotally, through odd stories such as this. They knew, as the Mandeville author writes, “according to the opinions of ancient wise men,” that the planet was round and its circumference was 20,425 miles. He gave the Ptolemaic measurement found in at least a few of his known sources, but actually, he humbly differed, it was bigger. And he was right.

So it was that one could circumnavigate the world in this way; however, he wrote, hardly anyone would ever choose to do so. What with the many ways and territories through which one must pass, getting lost was all too likely. And then there was the incredible distance, such that one climbed from England toward Jerusalem, for so it was then thought of as an ascent, reached the holy city where a spear at midday cast no shadow, and then descended toward the lands of the Mongol khan and Prester John. And as one did so, one experienced daylight in those lands just as it was night in England, for the two places were opposite and in step with one another, the one directly below the other.

As we started this series leaving the one, we’re approaching an ending with the other. We’re travelling through more of the medieval world from the known and well-trod to the more fanciful, places like the island where dog-sized ants guard piles of gold.

The author shows us the Central Asian steppe. Tartary he terms it, “a truly wretched region: sandy [and] hardly fertile at all,” with “extremely wretched people [that] have a wicked nature,” and equally vicious, causing death to human and animal alike. There is Russia and the kingdoms of Krakow and Lithuania, lands with waters that are crossable in winter when they freeze over, demanding hard travel “in carriages on sleds and carts without wheels,” access only to the provisions one has brought along. There are places where the sun rarely shines and it is too cold to live. Elsewhere, in the region of the Black Sea, there is a place where it does not shine at all.

This was a place also visited by Alexander in the romances and described by Marco Polo, a place where there is no light that anyone can see by and so nobody ever dares go in. Strangely, those who go near are said to hear sounds from within: horses neighing, chickens clucking, and the chatter of human conversation. They know that people must live within but they know not for certain what kind or where from, though there is an associated legend that they are descended from the people of a Sassanian king, trapped there by God in what the text describes as a miracle.

Mandeville describes the four rivers that spring forth from paradise: Ganges, running through India with its precious gems, gold sand, and aloe wood; the Nile, through Ethiopia and Egypt, ever turbulent; the Tigris, meaning “swift-running,” in Asia and Greater Armenia; and the Persian Euphrates, meaning “growing well” for the fertility it brings. He even goes so far as to describe Paradise itself, though he at least admits to not having been there, only relying on the words of wise men.

Paradise is the highest region on earth, he says, high enough to remain untouched by Noah’s flood, high enough to nearly touch the moon, and around it its walls. They’re so overgrown with something like moss that their actual material is impossible to say, and entry past them is no easier.

No mortal human can go there, which is not particularly surprising, but it’s not for the reasons you might think. It’s not a theological issue. Paradise is on earth, so it is reachable. But it’s difficult, very difficult. There are “wild animals in the desert and … mountains and rocks which nobody can cross.” You can try to reach it by river, but then you need to contend with “great currents and huge waves that no ship can navigate or sail against.” Many had tried, but they’d “died of exhaustion from rowing, some became blind, some became deaf because of the din of the water,” all very much mundane matters of this world, before we finally get to the conclusion: “nobody can get there unless by the grace of God.”

So, maybe no trips to paradise then, but other regions were more approachable.

There was Tibet, with its fertile land sounding like those closer to Mandeville’s birth, brimming with wine and grain, and its fascinating snippet of distant, poorly understood religion. It’s people lived largely in timber tents or, in its main city, in structures strikingly built in bricks of black and white, and none of them were willing to spill blood of any kind for love of an idol they worshiped there and for their quote/unquote “pope, whom they call[ed] Lobassy,” a man followed by all the region’s clergy who were presumably Buddhist monks of some kind.

There was a large land, owned by a rich man named Catolonabes, a massive property containing a place we’ve visited before on this podcast, a “sumptuous, well-fortified castle on a mountain.” The castle boasted sturdy walls, and within them a lovely garden full of fruit trees, sweet-smelling herbs, and beautiful flowers, bubbling streams, pleasant halls, and richly appointed chambers of azure and gold. There were all kinds of beasts and birds to distract the senses and some that were animated by clockwork machinery, to entertain. It was another paradise of a kind, a false kind, and this might start to sound familiar.

There were three virgins, beautiful of course, and young men too, all in golden clothes; he would tell people they were angels. There were three gem-studded fountains, that, through underground conduits, he would cause to flow with whatever he wished, one wine, another milk, the last honey. And indeed, the text tells us, “he called this place Paradise.”

So what did he do with this “paradise?” Well, he’d bring in young men, “some knight or squire,” and he’d show them the magic of his garden. He’d give them strong drink; instruments would be played by unseen musicians; he’d tell them they were witnessing heaven, that this was where God sent those who had served him best, after they had died. All they had to do to regain entry, to remain there forever - all they had to do, was everything he asked them to. Specifically, that meant killing some local noble or enemy, which the young men did, happily, fearlessly, for, knowing what awaited them, they had no cause to preserve their lives. They welcomed death and all of the luxuries that it would bring.

Eventually, the text tells us, the most powerful families of the region had realized what was happening and banded together to kill the man. They had assaulted his fortress and destroyed both himself and his paradise, “not so long ago.” You could still see the site of the fountains, the ruined shells or foundations perhaps, but nothing of value there remained, no clockwork birds, no golden chambers, no gems or angels, milk or honey. All it held that had made it heavenly had been plundered or torn down to broken remnants, and only the stories remained.

As I mentioned, we’ve heard this particular story before.

This is the story of the Old Man of the Mountain, of the Syrian Nizari Isma'ilis, the Assassins, often thought to have reached the Mandeville author via our friend Oderic though there are some details which suggest an additional source, and indeed there were no shortage of available western literary sources by this time - Marco Polo, Jacques de Vitry, Benjamin of Tudela, and Arnold of Luebeck - but maybe the most interesting aspect of this version is that there’s no mention that the lord of the mysterious mountain fortress is a Muslim, a pretty significant omission. It reads instead as a depiction of a kind of Christianity, of a false preacher; we’re reading of a Christian heresy here rather than an actor within an entirely different religion, a heresy too many within that religion.

And it’s worth noting that the Assassins seem to have by this point entered the realm of literate public knowledge for Mandeville’s audience. There were already examples enough of crusader lords killed by them, kings declaring their fear of them, and there were also already allusions being made in poetry, Provencal writers who compared their enthrallment to their beloved to the assassins’ unswerving loyalty to their master. “You have me more fully in your power,” one said to his lady, “than the Old Man his Assassins,” which I think is really fascinating, these people who were hated and/or feared by orthodoxies of both Islamic and Christian belief, used to illustrate a kind of admirable commitment in the very earthly sphere. But like Mandeville, we should journey on.

We’re going next somewhere our author says he went himself, says is not very far from the Old Man’s mountain, somewhere he tells a story of that sounds extremely similar to a place we went in the Mongols’ series of episodes. “Some call it the Enchanted Vale,” the text says, “some the Valley of Devils, some the Vale Perilous.” It reminds me of Friar William’s description of the place, on his way to Mongol Karakorum, where his guide begs him to pray for safety because they’re entering a place where demons are likely to leap out and disembowel the unwary rider. Mandeville gives it a little more detail.

There are intense storms, and strange and terrifying noises like those of kettledrums and horns, with no apparent source. There are devils, always have been, and some say there is an entrance to hell. It all sounds like a place that makes you wonder, why would anyone go there? The answer, of course, was silver and gold.

It was the promise of such riches that pulled people there, many who went ending their lives strangled by devils, few returning, though clearly some did, to tell of the rock and the centre of the valley where the head, down to the shoulders, of a devil was visible, “utterly repellant and horrible to see.” And I’ll read the text’s description here in full.

“There is nobody in the world, Christian or otherwise, brave enough not to be terribly afraid should they see it. He looks at everybody so piercingly and so wickedly, and his eyes are so fast moving, flickering like fire, and he changes his countenance so often, that nobody dares for all the world to approach. Also, lots of flames of different colours come out of his mouth and nose and sometimes the fire stinks so much that nobody can bear it. However, [as was the case for Friar William], good Christians who are secure in their faith can go into the valley without harm and, as long as they confess properly and they bless themselves with the sign of the Cross, devils will not injure them.”

Naturally, our author was among those “good Christians.” A party of fourteen went in, among them two Franciscans from Lombardy who sang mass and gave communion, but still only ten came out with no one aware of what had become of the missing four.

Those who had made it out, told of surviving horrific storms that threw them to the ground. They told of precious gems and metals in abundance, though they wouldn’t touch them for fear of the aforementioned devils, and for uncertainty that what they saw really were gems and not some kind of devilish illusion. They were equally uncertain about the dead bodies, a multitude of them, as if two great kings had joined in battle there in the valley and left both armies lying on the ground.

It was a grim thing to be sure, one which the text makes clear was a daunting ordeal that had worried them deeply before they began, and indeed it was one which in some versions featured tromping over the wailing corpses of those who had gone before.

However, despite my repeated references to Friar William here - and there are certainly similarities, and indeed William was also a source for the book - he is apparently not the friar that this story is ascribed to. That is, again Odoric, and in a pretty funny little touch, the Mandeville author actually seems to include Odoric in his telling - remember those “two Franciscans” - as if they were companions there in the perilous valley, facing danger side by side, not originator and imitator. The author unobtrusively connected the two, and the connection would in some instances become stronger over time.

In one German translation of the Odoric text, the friar would actually be described, quite hilariously, as “faithful Brother Odoric, companion of the knight Mandeville in India,” the two having apparently shared in bold adventure. A later translator pauses in the telling of the Mandeville anecdote to report that they’ve seen the story confirmed by a work in the Franciscan library, apparently that of Odoric himself adjusted over time to comply with Mandeville’s account. These texts were alive and reactive, like planets in one another’s gravity, but simply having been first, been original or authentic as we might term it, did not make one the sun around which the others circled.

Mandeville, whoever he was, was not first. He didn’t go to many of the places he said he did. It’s possible that he went nowhere at all, possible that he traversed some much more modest itinerary - not all the material is easily identifiable as coming from one particular pre-existing source or another. But if his was not to be the original it would be to have lasting impact quite beyond many that were, reaching a kind of bestseller status that his sources largely would not. And this was not entirely undeserved.

Maybe he had not really served the Egyptian sultan or observed the religious festivals of India. Maybe he hadn’t resisted the lure of demons in that infernal valley or looked upon the splendour of the Mongol khan’s Chinese palace. Maybe he hadn’t even gone so far as to make the pilgrimage to the holy land. But he had created something of his own.

It was a collage, yes, but not one which simply parroted the reports of others. At times, he’d disagree with his sources, and this was, admittedly, not always for the better - see for example how he insisted, against the word of his source, that the pyramids were grain storage facilities. At times, he’d reframe them or put them to the new purpose, react to them with a new opinion - his own spin on Odoric’s religious takes are an example of that.

As I’ve mentioned a few times on this podcast, the use of another’s material cannot really be understood in the way we think of plagiarism. It was part of how one fitted one’s work into the established body of knowledge. However, in this case, the close resemblance to Odoric’s writing was noticed and to some effect. Odoric’s less widespread work, both in spread of the text and in the breadth of geography it covered, was sometimes actually taken as that of one of Mandeville’s companions or even as itself being, out of the two, the one that was a copy. Mandeville’s account, though a fabrication, would have legs.

Medieval Mandeville manuscripts or their fragments survive in unprecedented quantities, and its popularity would carry over into the print-era. There were those who read it for its theological framing of the wide world or for its entertaining depiction of all the strangeness it contained, for morals and marvels. It was, for a time, taken as a pilgrimage narrative and then, shifting with the needs and interests of a shifting world, one of geography and exploration referred to by Columbus and Raleigh, a framing that would eventually lead to its fall from grace. As Rosemary Tzanaki concludes in her book Mandeville’s Medieval Audiences, “This was the attitude which was to contribute to Mandeville’s becoming a figure of ridicule, a ‘liar,’ once the age of exploration his work arguably helped to institute began to disprove his claims of Monstrous Races in the East.” As she puts it, “history, romance, and religion were thrust into the background,” as the book began increasingly to be consumed and then judged as a piece of travel writing that reported on the actual geography of the world.

Still, the work didn’t entirely disappear. One copy features substantial annotations likely written by the famous 16th-century astrologer John Dee, and in the late 16th-century it was read by the heretical miller Menocchio, star of Carlo Ginzburg’s microhistory The Cheese and the Worms, a book that I haven’t read in a long time and had entirely forgotten any mention of Mandeville there. But Menocchio was burnt to death in 1599 for his views and inability to keep them to himself; the Mandeville material was removed from the 1598 edition of Richard Hakluyt’s collection of travel writing; and in 1628, Mandeville was referenced in English playwright Ben Johnson’s work, The New Inn, belittled there as describing “colonies of beggars, tumblers, ape-carriers … savages [to whom the speaker] was addicted.” Our text had fallen some distance, but it would never entirely go away, and now, some six and half, closing in on seven, centuries later, we get to read it still. And it’s still changing as new translations are issued, based on one edition or another, as new people look to it for or with new information.

There is more to the book than we’ve seen here. There were other places to go, ones where seventy foot giants lived, or women with jewels in their eyes who could kill with a glance, but I won’t be getting to all of them. I’ll steer this episode toward an end with a passage from where Mandeville ends it.

“There are many countries and marvels I have not seen, therefore I can’t describe them correctly. Moreover, in countries which I have visited there are marvels that I haven’t described, as it would take too long, and so consider yourself sated now with what I have said. Also, I wish to say no more about such marvels as are there, so other people might travel there and find new things to describe, things I haven’t mentioned or described, because many people very much like and desire new things.”

End quote. For Mandeville, the marvel was not something from beyond the real. It was the most important and instructive feature of it. And he continues.

“So I, John Mandeville, knight, who left my country and traversed the sea in the year of Our Lord 1332 and have passed through many lands, regions, countries, and islands, have now come to rest; I have compiled this book and had it written in the year of Our Lord 1366, that is thirty-four years after my departure from my country, for I was travelling for thirty-four years.”

The story-telling wasn’t quite done there. Our guide tells us he went home via Rome, that he shared his book there with the pope and told him of all the strangeness he had seen, that the pope gathered up a council of all his wise men, including many from the world over, and that the pope and his council concluded the book and all it contained was true. “Therefore,” he said, “the Holy Father the Pope has ratified and confirmed my book in all topics.”

So there you go. Mandeville says he saw it, and the pope says it is so. Feels right to end things there.

I hope you enjoyed these Mandeville episodes. If you’re feeling like we’re missing something from the series, maybe someone, then you’re right. I did indeed mention the name Prester John at points here, and yes, Mandeville does indeed visit his lands, but I’m not skipping it over. I’m just setting it aside for a moment, to get into it with an upcoming series featuring the legendary priest king himself and the efforts to find him. So, coming up, Prester John.

If you’re listening on the Patreon friar feed, then do keep listening for an early 13th-century tale of flying ships and other marvels.

If not, I’ll talk to you soon. Take care of yourselves, everyone.